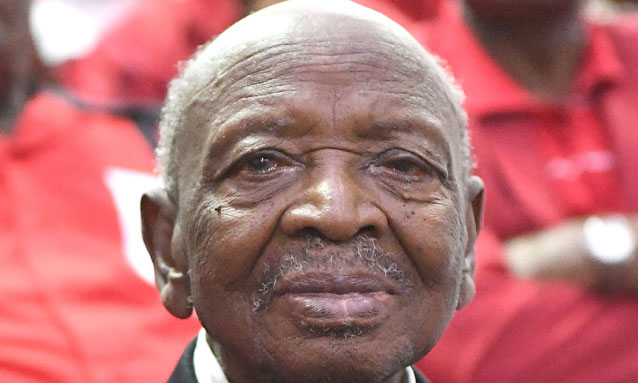

If the Democratic Republic of Congo can lay any claim to normalcy in 2021, it is because 21 years ago, “a gruff [Motswana] man then not far short of 80” barnstormed across the world to help end what was then Africa’s largest armed conflict. That man is Archibald Mogwe and the description is from “A Sacred Cause”, a book by Philip Winter, who worked alongside Mogwe during the Inter-Congolese Dialogue (ICD) between 2000 and 2003.

Their principal was former President Sir Ketumile Masire whom the Organisation of African Union (later renamed African Union) had asked to facilitate peace talks between warring sides in the turbulent Southern African nation. Mogwe was Masire’s right-hand man and Winter the Chef de Cabinet – French for “Chief of Staff.”Mogwe’s first assignment in mid-2000 took him to New York and then Libya, where Winter encountered him in a luxury tent waiting to see Colonel Muammar Ghadaffi. Winter writes in the book:

“With little ado, he left Libya and flew through South Africa to Botswana. His wife Serara handed him a suitcase of clean clothes and he took off straight away on a direct flight to New York, composed his speech on the plane and delivered it without a hitch, complete with a line inviting the ambassadors of that controversial body to visit Botswana and sample for themselves its famously tasty beef.

Men half his age would have struggled to cope, but, in his eightieth year, he seemed unfazed, complaining only that by the time he arrived in Botswana, after 24 hours of travel, he was stinking and sorely in need of a shower and clean clothes.”

In the DRC itself, Mogwe toured DRC’s 11 provinces as well as 19 cities and towns, meeting governors, international organisations, religious leaders and civil society representatives. With this tour, Botswana’s first Permanent Secretary to the President, former foreign affairs minister and Ambassador to the United States, introduced the long-suffering Congolese to democracy.

“The exercise was, as far as we could tell, unprecedented,” Winter writes. “More than once the team was told that this was the first time their local interlocutors had ever been consulted about anything by people coming from Kinshasa. Certainly, no Congolese politician had been able to tour the whole country and consult constituents on this scale for a very long time.”

Four days before Al Qaeda attacked the United States (September 7, 2001), Mogwe and Winter met the Assistant Secretary of State, Richard Armitage. They had wanted to meet his boss, Colin Powell, but he was out of the country. That evening, they unwinded at a Washington D.C. restaurant, where a belly dancer draped a scarlet scarf across Mogwe’s head. The elderly man bore this encounter “with great fortitude and managed to look quite unruffled” and “the two Batswana bodyguards were intrigued.”

A similar relaxed moment that Winter recalls in his book is of a dinner that then Vice President Ian Khama hosted at the Gaborone Sun Hotel (renamed Avani Hotel) when the ICD convened in Botswana.“At around 10 p.m., [Masire] took to the dance floor with his wife, Rre Mogwe bore Malebogo [Bakwena], the Office Manager, off in the same direction and not to be outdone, I took Selwana [Bagwasi], the office driver, to dance with me. The delegates cheered.

They had been used to a remote, stiff formality from their leaders on public occasions and this was an unexpected glimpse of a more democratic culture, where security did not rule out personal contact between leaders led.”

That was in 2001 and 30-year old Joseph Kabila had also jetted into town to attend the peace talks. At the time that the former first family was torching the G-Sun dance floor, Kabila was back in Kinshasa, having left in a huff and puff. His expectation was that upon arrival at the Sir Seretse Khama International Airport, he would be welcomed with an elaborate arrival ceremony replete with a 21-gun salute and a guard of honour. However, such reception would have created the impression that the Botswana government was legitimising a rebel leader who lacked any legitimacy for presidential office and complicated Masire’s job as facilitator. In the end, and despite a plethora of odds, the ICD managed to set up a transitional power-sharing government and paved the way for the 2006 elections. Those elections brought the DRC to where it is today.

Mogwe, who lived on a farm in Hildavale, died last Thursday at the age of 99. May His Soul Rest In Peace.

To read more about Archie Mogwe: http://yourbotswana.com/2019/04/07/15-facts-that-every-motswana-should-know-about-one-of-botswanas-founding-fathers-archibald-mogwe/

Source: http://www.sundaystandard.info/as-masires-aide-mogwe-helped-put-out-drc-inferno/