It’s no secret Botswana has issues with widespread unemployment due to lack of opportunities, as such there’s a drive to create opportunities. As it stands, the drive is primarily focused on providing opportunities for the youth, which incredibly ranges from people aged between 18 – 35 years old.

Naturally, the majority of the youth within this age bracket are graduates in excess of somewhere around 80,000+. However, another main-stay on all manifestos (past and present) is the eradication of poverty. Many of those who fall into this category are not graduates or youths. While I have no statistics, Botswana’s population is approximately 2.2million, so I would guess the figure of those living in poverty is much greater than 80,000.

What about the poor?

In my own humble opinion poverty is a bigger issue and eradicating it should be a more pressing matter. Creating opportunities specifically for the youth excludes a much larger percentage of the population, whereas creating opportunities for everyone effectively and logically can kill two birds with one stone.

One of the reasons I compare unemployment to poverty is because in reality, there are many folk with jobs and yet still live in poverty. I wonder how many graduates are living in poverty? Graduates may be unemployed, but many come from decent backgrounds and still have the comforts of living at home. The issue of unemployed graduates is not trivial, but realistically, it’s not new as it’s the case on every continent. It is alarming, but I wouldn’t class it as an epidemic, but rather a sign of the times.

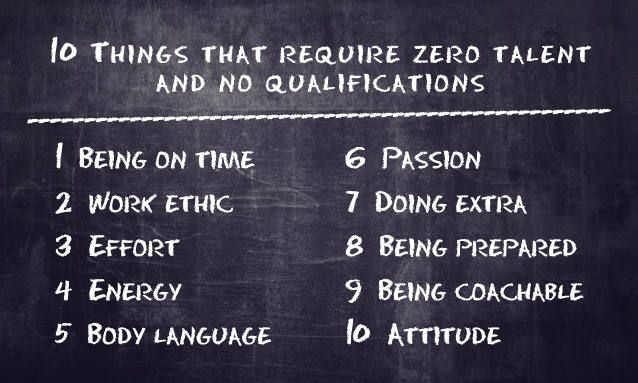

The reason there are folk employed and still living in poverty is because there are two groups – those who have qualifications and those who don’t. Those without have little option but to work in menial jobs, which are low income, zero prospects and zero benefits. Menial jobs pay the minimum wage, which is so bad it’s extremely difficult to survive on and impossible to save for the future or pay for a college education. It’s a generational cycle that repeats itself.

Imagine working 72 hours a week (or more) and earning less than P2,000 ($190/£145) every month. It’s shocking to know there are many earning less than P1,000 per month! You could argue, what’s the bigger travesty… unemployed youths or the fact such low salaries are ensuring people remain in poverty?

When you categorise those with qualifications and those without, as a society, we inadvertently paint the unqualified with the ‘thick brush’ and this is unfair. They are deemed lesser members of society, which is not good for self-esteem and it creates segregation that brings about a social divide.

You won’t find many graduates working in menial jobs in Botswana because they are considered over-qualified. Even if this wasn’t the case, many graduates would likely choose unemployment over these types of jobs because of the stigma associated with menial jobs. It is a catch 22, but on other continents, graduates don’t have the luxury of choice and so take on menial work just to get by.

During my first and second years at university, I was a cleaner five nights a week. Upon graduation, I struggled to find a job relevant to my degree, so for two years, I worked at a supermarket. I was earning approximately £435/$570 per month after tax, which equates to around P6,000 and that was close to 20 years ago! The cost of living has increased the world over and life in Gaborone is expensive.

How important are qualifications?

Back in the day my parents and grandparents would labour the virtues of a good education leading to a good and stable job. But it doesn’t really work that way anymore. To some extent, it seems unfair to raise children with this belief, as any parents 10 years north of the youth bracket were raised in a world that no longer exists. It’s the 21st century and the professional environment has evolved.

These days you need experience to get your foot in the door and any potential training/development takes place during employment. Of course a good education is a strong foundation, but (depending on your chosen career path) academia is not always a key factor and does not guarantee a job.

Society views the unqualified as less intelligent, but many are simply less academic. They watch current affairs, they read books and newspapers and they have meaningful and insightful discussions. There’s one thing I’ve noticed in Botswana, there are many security guards that are dual employees. You go to the bank, post office or mobile phone shop and (more often than not) the first person to assist you is a security guard.

Admittedly, some are more proactive than others. Those who are proactive seem to know the business operations of where they work rather well, probably just a well (if not better) than the actual employees. They are polite, knowledgable, efficient and (considering they don’t have qualifications) their English is pretty damn good. The vast majority don’t have smart phones or Facebook accounts, so they don’t stand around taking selfies and remained focused on their job.

But should a vacancy at that establishment become available the security guard is unlikely to be considered because he or she doesn’t have any qualifications. Yet they have proven their value to the company, proven themselves to be loyal, hardworking, trustworthy and possess the ability to learn. Someone who isn’t academic isn’t necessarily incapable of learning or being an exemplary employee.

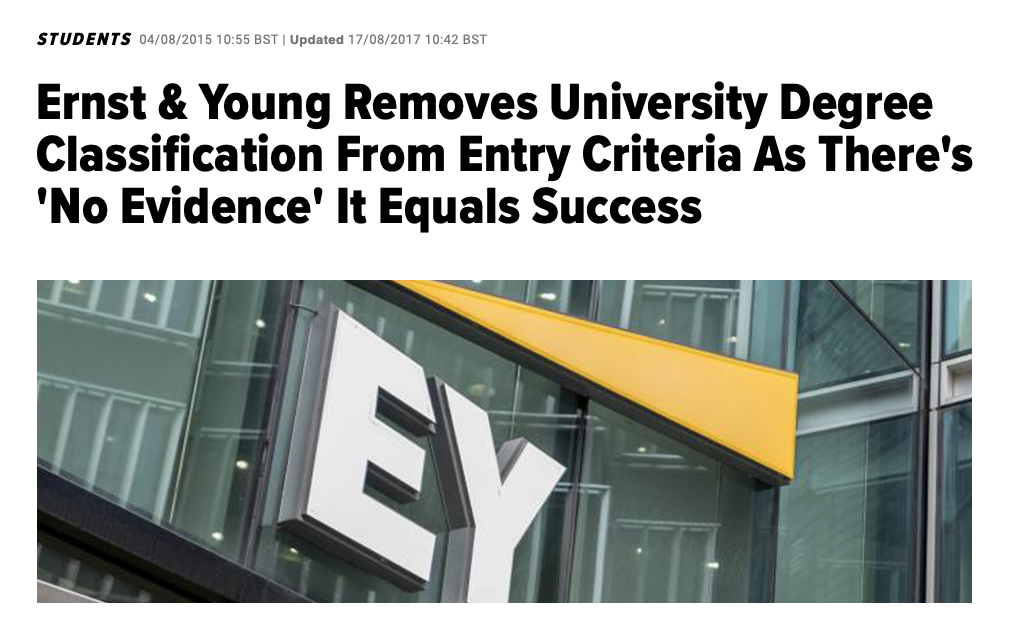

Even a large corporate giant such as Ernst & Young (EY) has changed its recruitment criteria. The company now plans to remove degree classification (and the equivalent of three B grades at A-Level) from the entry criteria when hiring. They have found “no evidence” that qualifications equal success in the work environment. Instead, the company will use numerical tests and online “strength” assessments to assess the potential of applicants.

“The changes would open up opportunities for talented individuals regardless of their background and provide greater access to the profession. Academic qualifications will still be taken into account and indeed remain an important consideration when assessing candidates as a whole, but will no longer act as a barrier to getting a foot in the door. Transforming our recruitment policy is intended to create a more even and fair playing field for all candidates, giving every applicant the opportunity to prove their abilities.”

Maggie Stilwell – EY’s Managing Partner for Talent

Botswana (and probably most of Africa) hold on to the belief that the best route out of poverty is a good education. But how are those born into poverty to pay for an education? Charity maybe? How do we even define being well-educated? Is a vocational qualification inferior to a university degree? These days degrees are diluted and cheapened when you consider the many variations and obscure subjects that can be studied to degree level. There’s also a lack of diversity in Botswana because many graduates acquire qualifications in similar fields, so the market is saturated with a lot of the same.

What about the forgotten generation?

We must also remember there are people not categorised as ‘youth’ and this is a forgotten generation. This generation didn’t grow up with youth funds or the prospects and resources the youth have at their disposal today. This generation has been struggling for decades. Many of them have children (or want to have children), mortgages, loans, no retirement funds and so their futures look bleak. It is also the culture in Botswana for children to financially support their elders, but many simply can ill afford to do this.

An alternative ‘drive’ would have been to create opportunities for those aged between 25-45 years old, which accounts for a large majority of the forgotten generation. There’s a natural transition between childhood and adulthood and that period starts when you leave the educational system. This is when you experience real life and an appreciation of the hardships endured by your elders.

The safety blanket for the youth would be the knowledge there is support and funds available upon reaching the age of 25. The truth of the matter is there is a huge risk providing people as young as 18 with grants in lump sums, which is essentially free money with zero accountability. Lest we forget, the money given is tax-payers’ money paid by the forgotten generation. The majority of the youth will be beneficiaries of a system they haven’t yet contributed to, and yet (for many) it has already covered the cost of their education.

It’s common sense that with age comes maturity and the self-awareness to live within your means. Many of the youth have soft and innocent minds. They could be easily influenced by evildoers and make poor judgements with a ‘get-rich-quick’ mentality. Fast money and living in the here and now is what appeals to everybody in their youth, but mistakes made in our youth serve as lesson learnt. The impacts are relatively small, enabling us to move forward a little wiser.

In my mind, it’s better to provide opportunities for the forgotten generation. We can’t focus on quantity over quality, it’s impossible to find employment for 80,000+ people in the short-term. But providing opportunities and funding for the forgotten generation is more beneficial. Just one successful business can create numerous jobs… two birds, one stone. More mature individuals can mentor, train and pass on experience to the youth, but it also works both ways because the youth can teach old dogs new tricks. I personally don’t believe it will work the other way round, as the youth are less likely to employ their elders.

What does the future hold?

The Botswana Government is doing all it can to attract foreign investment, which will hopefully create much-needed employment opportunities. There is light on the horizon for Botswana’s youth, but what about Botswana’s forgotten generation? Will circumstances really change for the poor and unqualified with foreign investment, or will it just mean more low income, menial jobs?

If we focus too much on the youth, there’s the risk that the youth will become accustomed to being assisted or reliant on institutions. They will transition from the haven of education into another haven where opportunities are waiting for them. It’s like keeping an animal in captivity from birth, then releasing it into the wild and expecting it to survive. The government mentioned ‘youth’ and that seemed to kick-start a trend with Youth Expos, Youth Conferences and Youth Summits popping up everywhere and Youth Training, Youth Entrepreneurial Programmes and Youth Funding being readily available. It’s great, don’t get me wrong, but the real goal should be to create jobs and opportunities for EVERYONE.

A government should not be the largest employer because the funds used towards labour costs are funds that could be used to improve public services. The private sector needs to step up and take a leaf out of E&Y’s book. Recruitment is somewhat skewed and needs a less rigid approach. Roles and responsibilities cannot be combined – a marketer can’t also be a graphic designer, human resources or customer service can’t also be accountants, etc. Many organisations (private and government) can create jobs if they adopt a modern mindset and a modern approach to business… and requesting applicants have 5-10 years experience is ridiculous.

The real world is a level playing field. A security guard should be considered for promotions and be allowed to compete if he or she has proven to have all the attributes required. I’m not suggesting a revolution in which all security guards (or all those in menial jobs) should be employed in better jobs. I’m not suggesting we should disregard the youth, but is it fair to disregard the forgotten generation? Where policies and procedures are concerned, change needs to start at the beginning and move forwards. But in the context of people and improving lives in Botswana, change needs to start at the end and work backwards.

I do believe a radical improvement in the minimum wage will have a fast and far-reaching positive impact on many lives. I think we need to stop the social divide, stop with the “who you know” culture, start to see everyone has potential and gauge people on merit. Graduates and youths are not restricted to the borders of one country, be it physical or virtual, but many of the forgotten generation are. Many of the youth have the skills and the resources to create opportunities for themselves and many are doing exactly that.

To empower a nation is to make them feel opportunities are available for everyone. To develop a nation and eradicate poverty is to stand united and actually provide opportunities for EVERYONE.

By YourBotswana writer