May 15, 2023

A day in the life of a trainee safari guide might include elephants, a dawn symphony and micro-wildlife. Short courses offer a taster.

Waking up naturally at 5am, I unzip my tent and watch my grubby feet as I step out into the Botswana bush. A deep wound on the horizon bleeds violet into the darkness, and while I can’t see a single creature, the thicket is alive with activity. I take a seat in a camping chair under the tarp, twist my matted hair into a crocodile clip, close my eyes and listen.

At first, all I hear are cicadas, fizzing like lemonade among the long grass. Then the cape turtle dove offers its distinctive warble, which sounds like “Botswaaana”, “drink laaager” or “work haaarder”, depending on who you ask and what mood they’re in. The grey go-away bird makes me laugh with its characteristically loud and nasal “kweh”, which to me sounds like the condescending “wah” of an adult mimicking a baby. Then, suddenly, a deep howl breaks through the birdsong.

An hour later, standing around the fire pit with a mug of coffee pressed between my palms, I try to recreate the sound for our field guide, Mike Anderson. “Baboons,” he says, and is polite enough not to laugh.

I was on day three of six at a temporary camp in a remote area of the Northern Tuli Game Reserve, on the border of Botswana and Zimbabwe. Natucate, a travel company offering meaningful experiences, organised the trip for me with EcoTraining, which runs accredited courses in safari guiding and wildlife tracking across Africa.

While most people have fantasised about quitting their 9–5, packing a bag and leaving the country in search of adventure, I doubt many have considered safari guide as a feasible career change.

However, EcoTraining has trained around 150 people in the last year, and since the pandemic, the idea of a “conscious sabbatical” has risen exponentially, with more and more companies offering grown-up gap years to their employees.

During a short stay in South Africa, before crossing the Botswana border, I spoke to one of Eco Training’s students, Kate, who has left behind her life in London to work and live in the bush while she trains.

“I spent a lot of time in Africa as a child and even though I went to school and university in the UK, there was always something drawing me back to nature and African wildlife,” she said. “It gets under your skin.”

Kate told me students are a mixture of ages and from all walks of life. There are grandparents, a married couple, a mother-of-two pursuing her university degree, a PhD candidate, a novelist and a government clerk. Some are seeking careers in field guiding, others are interested in wildlife conservation and some aren’t quite sure what they’re doing yet.

“People are looking for a form of connection, whether it’s to others within the community of students, themselves or the natural world. But it’s often all three,” Mike said.

To reach our temporary camp in Tuli, I flew to Johannesburg in South Africa before crossing the border by car and then cable-car, into Botswana. Mike and Dries Kemp, our other field guide, greeted us sporting wide-brim Stetson hats and .375-calibre rifles. From there, we drove for three and a half hours into the bush.

The Tuli reserve covers all the land north of the Limpopo River and due to an unusually high rainfall, the thicket was lush and green. Our muddied Toyota 4×4 bumped and shuddered across fields and fields of yellow Devil’s thorn and as far as the eye could see, there were animals. Impala, elephants, zebra, giraffes, warthogs – so many species that it didn’t feel real.

I was one of the first to stay at a little collection of dome tents in the middle of the bush which, when the trip came to an end, was packed up and driven away. Eventually, it will become an EcoTraining camp for aspiring safari guides.

Falling into a routine of early mornings, communal meals and game drives was easy. We had bucket showers, but the water was rationed (keeping hydrated trumped keeping clean) – so I embraced the dirt. Away from screens and other distractions, small talk didn’t last long in my group. We were over-familiar, co-dependent and rarely out of each other’s sight, much like a troop of baboons. I can only imagine how much you’d bond, and how challenging living in such close quarters must be, over the course of a year.

The game drives and walks involved tracking paw prints, listening to the bush and pointing excitedly at an overwhelming variety of birds, plants and animals. Occasionally, we’d stop under towering leadwood trees for refreshments and quiet chatter. We’d shield from the sun behind one of the giant trunks, which were cracked into a network of rectangles.

One of the most beautiful animals I encountered was the grey ghost antelope, or the greater kudu. Brown-grey in colour with a white stripe running along its spine, it looks like a mystical creature from CS Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. The grey ghost is a master of camouflage and seems to mysteriously appear and disappear among the thicket, as if a figment of your imagination.

Elephants are easier to spot and as herds passed our vehicle, I was reminded of Colonel Hathi’s March in The Jungle Book. Shortly after a downpour, we watched infants, just weeks old, cooling off in puddles before finding shelter under the legs of females. When standing alone, elephant calves are a comical sight, with out-of-control trunks and fuzzy hair on their heads.

But while the large animals are magnificent, I found the micro-wildlife just as fascinating. After dinner one evening, an electrical storm hit the camp and despite walking in the footsteps of lions just hours earlier, it was the first time I felt scared. We retreated to our tents and as I bent down to unzip the canvas, my head-torch illuminated a solifuge, which is somewhere between a spider and a scorpion.

At around four inches long with a fat, tanned body and oversized jaws called chelicerae, my campmate made quite the first impression. I stood paralysed, watching it devour what appeared to be the remains of a moth. While not venomous, a solifuge’s bite can be nasty and is strong enough to draw blood. When it finished, it scuttled off into the darkness with surprising speed. I climbed into my tent and lay back on the mattress, full of adrenaline and unable to sleep.

The following day, we parked up the vehicle and crept through the bush on foot. Sitting on my heels and listening to Mike talk, I admired the purple-pod cluster-leaf (which smells like blue cheese) and the white button sedge. I watched like an eager child as the elegant grasshopper leapt beneath a white-stemmed Shepard’s tree. I followed a male dung beetle and observed ants breaking into termite mounds to steal eggs with military precision. As humans, we’re so often focused on macro-wildlife – the imposing giants and predatory cats – but there is a whole world thriving in the grass.

What struck me most during the trip is that to Mike and Dries, safari is more than just a guided experience – it’s an environmental education. Instead of an almost nervous fixation on seeing the Big Five (lion, leopard, rhinoceros, elephant and buffalo), we were gently taught to appreciate all aspects of nature. We discussed how human interference has negatively impacted ecosystems, and the importance of protecting our environment to ensure a sustainable future. We talked about the inextricable link between ecotourism and conservation, and the importance of our natural resources.

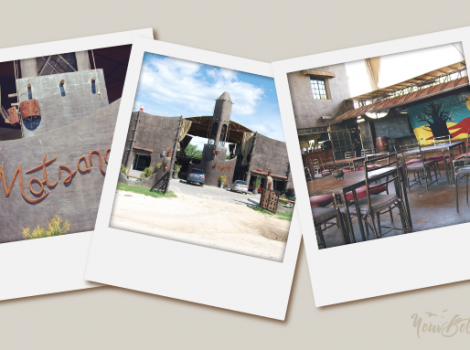

“EcoTraining provides an opportunity for modern people from around the world to visit and connect with their natural home,” EcoTraining founder, Anton Lategan, told me as we sat under the stars at Leopard’s Lair Bush Lodge in Hoedspruit, South Africa.

“As we begin to understand our natural environment, our modern stresses recede, our ancient facilities come alive, and we make peace with ourselves.”

Driving back to the border, I felt a knot in my chest. While I smelled like urine, looked like a Hobbit and was convinced stick insects were breeding in my top knot, nature had become to feel like a refuge. The vastness of the reserve, an unending maze, reminded me that we as humans are part of this resilient and connected world.

I looked out at trees colonising fertile mounds built by termites, sucking up salts from the ground and attracting a great diversity of life. The whole world is tied together by these natural relationships that make the air we breathe and clean the water we drink.

Back in England, I miss the calls of the go-away bird, and I long for a growl to pierce through the air each morning. I remember each dawn chorus, and I miss the symphony of rural Africa. Home in London, the city seems too quiet.

By Lucy Clarke-Billings