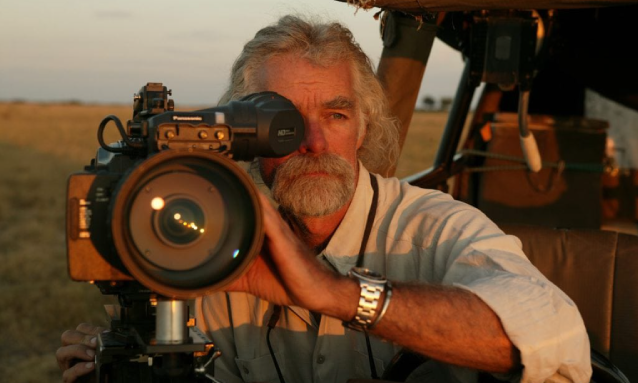

We all have our favourite safari destinations, but what makes this southern Africa country so special? We asked a man whose spent his life filming, photographing, and now fighting to protect the country’s wildlife: Dereck Joubert

I often ask myself why I love Botswana. It’s like asking anyone in love why they fell in love in the beginning. It is the lift of hair in the breeze, the fragrant scent that you can still remember from the first time you saw her, the sound of laughter that lifted your own spirit to the clouds. It is why I fell in love with Beverly, and with Botswana.

Even now I can recall the scent of wild sage mixed in with the particular elephant smells across the mopane woodland in the north, that no man’s land between the rivers that bustle with life in the dry season and the vast wilderness that sucks up thousands of herds and makes then disappear into the greenery each wet season.

I think it’s the sheer wildness of Botswana that holds us captive, a place where philosophers and poets have sought refuge to find their souls, to write, to reflect and to create.

We are, I believe, most of all, the storytelling ape — homo ‘scriptus’ perhaps, a new term instead of ‘sapiens’, that means wise ape (and sometimes I question this definition). We each write ourselves into our own stories, as heroes, main characters, and so we should. But it is against a backdrop of the purity of nature that we play best.

Years ago, Botswana made a strategic determination to develop a tourism model based on high value and a very low ecological footprint. “The Botswana model” allows for just that kind of silence when you need it most, the pristine, the uncluttered. And it is the envy of many other countries.

I recently walked along the edge of a typical Okavango thick-reed island and stopped suddenly as the tall sedges parted. A shaggy-haired creature stepped out and also stopped. As we eyed each other — him weighing up if I was a threat, me wondering how long the magic would last before he bounded off — we shared a silent contract. Birds waited quietly for one of us to break the spell. I was watching a rare sitatunga antelope, and then he dipped his head down and start nibbling on fresh shoots in the reeds. It was mesmerising. It was heartwarming; a moment of trust.

I believe that it is this trust between us and the natural world that rewards us most in life, in times when we are together, not opposing each other, not ploughing up rainforests or slaughtering wildlife or insisting that every acre pays for itself in dollar terms. It already pays. With humans making up 36% of animal biomass and our livestock about 60 per cent, that leaves just 4 per cent for wildlife. I would say it has paid a dear price.

Botswana is also home to about a third of the world’s elephants, existing peacefully so far. The Okavango is a place of peace and tranquillity for them. And they reward us lavishly, feeding our creative inner souls when we sit in their company, watching them at play or in the mud, with babies, old females and bulls enjoying the moment equally. Their example reminds us to be playful in life.

When they are ready to leave, every last one is helped out and the herd does a headcount before moving off. It reminds us to have empathy and caring. And when they communicate gently in soft rumbles, and sensitively give space to others, it reminds us to afford dignity and grace to those we interact with. If you are ready to be reminded of those life lessons, in amongst the elephants of Botswana is where you want to be.

The safari I encourage and imagine daily is not one chasing around in pursuit of the Big Five (a colonial hunting term for the most dangerous animals to kill, when in fact it seems there is a more dangerous one roaming the planet in numbers of 7.8 billion). Nor is it the more gentle approach of ticking off the well over 400 bird species in Botswana. These are certainly worthy exercises, but a safari is more about that connection I had with the sitatunga or the elephants, where silence is the common language, and the real achievement is in finding the best in ourselves to reflect to them as they nakedly wander in and out of our lives.

But a trip to Botswana, like one to Kenya and many other places, also affords the opportunity to meet the people who most interact with these natural places, to understand the ancient culture of living in harmony. We have been so inspired by this that Beverly and I help fund a school and are developing the Great Plains Academy, where guests will be welcome to give a lecture and experience the sparkle in a child’s eyes as she imagines the unimaginable in her life. This too is an expression of respect and trust, affording dignity and grace that I hope is the underlying reason to travel at all.

Look into the eyes of a large male lion and you will understand the connection we have to the wild, and why we need to preserve it. When I was born there were 450,000 lions. Today we have just 20,000 left, with only 3500 males. Leopards are down in a similar proportion, to under 50,000, and elephants have dipped below half a million. But their plight is mitigated by our collective will to do good. We have just moved 87 out of a target of 100 rhinos back into the wild in Botswana, with an exceptional breeding rate of 28 babies from that group. There is a global outcry when a dentist shoots a lion, a nation wants to slaughter elephants or baby elephants are shipped to China. So there is hope that we will ultimately do the right thing.

Why anyone would want to kill any one of these animals I have no idea, but the way we fortify the case for keeping them alive is through tourism, by spending time and money ‘investing’ in an industry that shows a real interest in seeing wildlife roam free, and at the same time providing respect, jobs and revenue to the people who risk their safety and security living near these wild places. So, why Botswana? It is because it is still wild and packed with a variety of amazing moments, but most of all it is because it makes the case to keep it so at a time when decisions are being made about the future of Africa and how we interact with it. Because it is a showcase for nature.

I live in Botswana because it is the place I can sit on a fallen-down tree and watch as elephants feed gently around me. I learn from them and welcome their lessons on how to better live my life. Most of all, I wish for this to happen to you on your next safari to Botswana. It changes your life.

This feature first appeared in edition 87 of Travel Africa magazine. To buy this issue, please click here, or to subscribe and receive future printed copies of the magazine, please click here.

Dereck Joubert is a conservationist, filmmaker, National Geographic Explorer at Large, and CEO of Great Plains Conservation