My parents are British and were living in Yorkshire. My father was a policeman and my mother a school teacher. My father had the opportunity to serve his country and government in the empire and decided that he would apply for a posting abroad. Initially, he applied for both India and Ceylon, but these applications were unsuccessful.

A post was subsequently advertised for Bechuanaland Protectorate, he applied and was accepted. At this time, Bechuanaland had 1 mile of tar road, and that was in Gaberone. At that stage they had 2 children, my eldest sister and I; a further 3 arrived in Bechuanaland, twin girls in Serowe and my brother in Maun. Part of the ‘deal’ included a return to England (‘home’ leave) once every 3 years.

A key decision that was taken by my parents was to bring their children up British as possible, for the simple reason they had no idea whether their children would enjoy Africa and want to settle there, let alone themselves. Consequently, our upbringing and education were focused to ensure that we could return to the UK if we wanted to.

The biggest challenge for my father was adjusting to policing small communities, which required a different skill set to Saturday afternoon football matches and Beatle’s concerts in Britain, neither of which he enjoyed policing. Bechuanaland was a very sparsely populated country in those days, and still is as Botswana. There were even less of those of European descent.

When we arrived in Maun, there were few other families of European descent. My father realised at a very early stage that you could not afford to upset the community in such an isolated, harsh environment as you never knew when you needed help yourself. The police also referred to October as the ‘murder month’; this was the time of year when the Ngamiland heat was at its most oppressive, and tempers frayed easily.

As an example of the tensions this could create, my father issued the game hunting permits and ensured these were complied with; not always the most popular duty with the hunters. The modus operandi of the police hunting patrols (which were days long) was at the end of the day they would camp with the last hunting party they had inspected. In one instance, the hunting party were surprised the police hadn’t joined their camp that evening as they were together in the late afternoon and decided as a precaution to drive back along their tracks to ensure there were no issues.

They came across two policemen with a tyre-tube around their necks full of water and carrying a police rifle. The police Landrover had broken down irreparably, and they decided that their best chance of survival was to try and walk to the hunter’s camp! They decided the essentials to keep with them were water and a rifle, for obvious reasons. The tubes were extracted from the wheels.

There was another incident one evening in town when, after a few drinks too many, two of the hunters decided to go flying in their aeroplane and have a bit of fun buzzing the town. Dad was incandescent about this, as not only did they not file a flight plan, but were also inebriated, behaving dangerously and a risk to themselves and the residents. But he did not feel it would be appropriate to take formal action for the upset it would cause. His strategy to enforce appropriate behaviour was to sulk for a few weeks, refusing to speak to anyone, and an apology was forthcoming; they couldn’t afford to upset him either, and they realised they had!

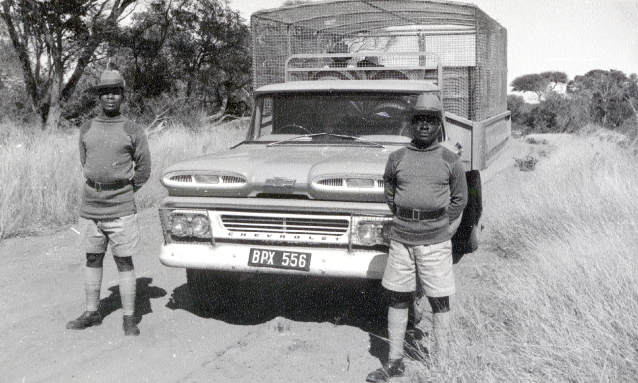

Below are videos of various Police patrols filmed by Donald Brooks

Written by Ian Brooks

Ian is Donald Brooks’ son. His father arrived in Maun in early 1962, leaving four years later in 1966. He was a police officer, trained in the UK, but working in the Colonial Service. His brief on being transferred to Maun was to sort out the ‘w’ element; there was a perception that there was insufficient regulation, particularly the hunting of the wild animals, and his task was to bring this under control.

Ian and his siblings were children while in Bechuanaland Protectorate/ Botswana; the younger 3 children were born in Bechuanaland Protectorate. The context is a combination of his own memory of life in Maun as a child, as well as various conversations with his parents over the years about the photographs and life in Botswana while they were there (1958 to 1968).