The following are recollections of the Midgley family first arriving in Ghanzi in September, 1950. The author was seven years old at the time and her brother, Alan, was soon to be nine. Ernest Midgley was to serve as District Commissioner in Ghanzi for seven years with the fulsome support of his wife, Olga.

It had been a long journey from East London, South Africa where we had disembarked from the ship that had brought us back from 3-months’ Home Leave in England. We drove north via Mafeking where we all had turns in the dentist’s chair. My mother had all her teeth extracted for fear of having no medical or dental aid available once we arrived in Ghanzi. My father went on to talk ‘business’ in the government offices in “The Camp” or “Imperial Reserve” – the offices and houses for the Resident Commissioner and his administrative team serving the country of Bechuanaland Protectorate.

Our new car, a Nash Ambassador, was a sleeping model. We camped and self-catered all the way, as the car ploughed its way up most of the length of South West Africa, stopping at Windhoek and on to Gobabis that had a dairy that received the milk from Ghanzi Farms. From Gobabis it was another two-days’ drive with the car often averaging six miles per hour following the twin tracks between the low scrub bush. We had picked up a puppy we called Sheppy from a friend who lived in Keetmanshoop, nearly a week before we reached our destination.

The car that stored the spare petrol on the roof was packed to the full. I was small enough to lie on top of the luggage with barely the space of thirty centimetres to the roof. No room to sit up. Alan sat between our parents, nursing little Sheppy on the bench seat.

After the final of many farm gates was opened, we turned right and there was the white plastered square building that would later be recognised as the Ghanzi prison. It would have housed no more than a dozen or so inmates. Thatched mud huts littered the dry red earth beyond. Happy, laughing people at the roadside waved at us as we drove by. Word will have got around that the new Molaodi was due to arrive, so there was great eagerness to see the new District Commissioner and his family.

His responsibility was to be administrator of 69,000 square miles. The Afrikaners had first arrived around 1900 in the area to escape the Rinderpest, a devastating cattle disease that had been the scourge of the Northern Cape Province. Not long before that, the chiefs had requested Queen Victoria to protect Bechuanaland Protectorate.

The chiefs, therefore, annexed Ghanzi Farms, the area set apart for white farmers to settle with their cattle, hopefully, to provide prosperity by bringing meat, milk and leather to the country, in an area never traversed before. It was to be an experiment. It was a success; for cattle farming to this day provides a vast income to the whole country. The hardy cattle provide lean and flavourful meat that is to this day much in demand for export. Chiefs the other side of the country had less interest in this allocated area, which still, of course, needed administration. The land teemed with wild animals and lions was the scourge of the cattle farmers.

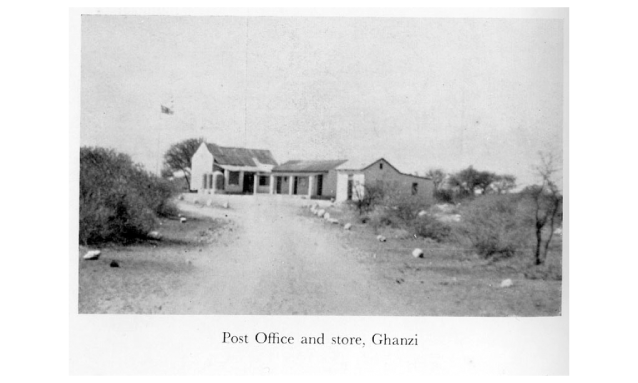

The track road went straight now, then down a dip over firm limestone gravel, then rising again up to the government offices. Marker stones, either side of the limestone gravel approach, were regularly whitewashed. What a relief after miles and miles of flat country with thorn bushes obscuring any view.

There were only the three houses for white government officials in Ghanzi camp, as it was called. That was all! No shops, electricity or medical aid. At the time of our living there, the population of the whole Ghanzi area was recorded as 240 white people; 7,600 black people, but they were hardly to be seen, so spread out they were in the area the size of Wales. The height of the bush also hid scattered small families of nomadic Bushmen who were seen only occasionally.

The British Union flag waved us a welcome. The patched corrugated iron roofs of the office buildings were baked and faded from the relentless hot sun. The small building on the right was the Vet’s office. My father’s office was on the left and an inter-connected door led to his assistant in the middle room and the largest room was the police office. A notice board was set out on the wall for public notices including wedding banns and official notices, all words that I could not yet fully read, although I did know some.

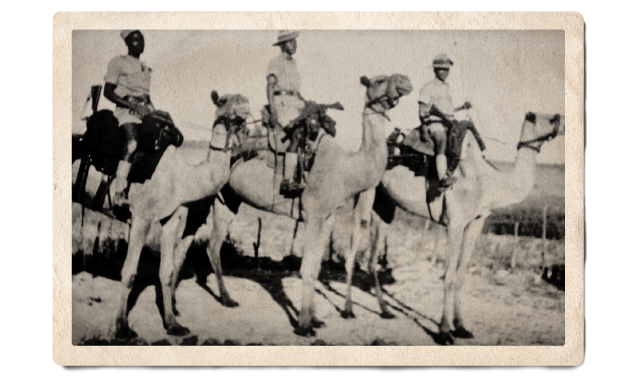

Then at right angles, in the far corner, was the cramped radio office next to a big room that was the police storeroom in which I remember the musty and pungent smell of saddle soap used on the police camels’ saddles. The floor was typical of the flooring of mud huts: dried manure mixed with sand. The flooring in the other offices was smooth red-polished cement. A single syringa tree had perfumed lilac-coloured blossoms. It provided scant shade to visiting trucks parking outside the offices. Behind the office were three tall leadwood trees. We turned left and drove on to our new home a couple of hundred yards further on.

“Yay! Alan cried out as he scrambled to see our new home.

“Not so fast, young man, both of you must help to unpack the car!” My mother needed the help. Of course, Alan ignored her, so I followed suit.

The policeman, Mr. Clark heard our car arrive in the silence of the late afternoon and came strolling over to invite us to have supper with them. Holding his hand was his cute little two-year old blonde daughter, Brenda. Our parents were grateful for this offer as the light was fading now as we were arriving much later than we expected.

The hard work of unpacking the car and putting the house in order will have gone over the tops of the heads of us children. Our heavy stuff, such as beds, wardrobes, chairs, the one sitting room carpet, the piano, lamps and paraffin-fuelled refrigerator had arrived in advance, when we were on leave in England. But I wonder to this day how we coped not having access to any shops. Of course, the Ramsden brothers whom we passed by a few hours earlier will perhaps have given us some fresh milk, eggs and bread. But we usually coped with powdered milk, called Klim; biltong, eggs and butter and the supplies that we will have bought in Gobabis too. We relied considerably on canned foods.

Mature grapefruit, orange and lemon trees and figs grew close to the house, as well as a grapevine formed into an arbour in front of the house that produced shade and small, sour grapes. The garden was well watered daily by the prisoners. My mother was soon to be found planting peanuts, pumpkins, melons, tomatoes, carrots, onions, cauliflower, cabbages and watermelon and extended the front garden, filled with butterflies busily visiting the colourful flowers. They are all gone now. The trees will have succumbed to some dreadful droughts since that time. Now today, it is just naked sandy soil around the house leaving no trace of our resourceful food supply and pretty flowers.

My mother was left alone in Ghanzi for several days at a time when my father went away to make his rounds in the district visiting the farmers. So whilst my father was camping out in the wilds, my mother would be the only white woman for a distance of several hours away. She did not drive and the roads were mere tracks between the bushes. She was actually quite nervous at her solitude and would keep a little brass bell at her bedside so that the servant could be called were she to need help. She used to set up ‘traps ‘ for prospective burglars such as putting a broom across the passage on the way to the bedroom. She put the broom handle just at ankle height.

“That will be bound to trip him up!” she explained.

Occasionally, the servant would accompany Dad on these trips, so I don’t know who would have heard her little bell! Although we had guns in the house, I don’t remember my mother ever handling one. They would have been solely for my father using them to shoot ‘for the pot’, which meant he would have taken them on patrol with him. My mother scoffed at the suggestion that she would be lonely. She said she was too busy! There was the garden to attend to, her letter writing; her contributions to the Mafeking Mail about events and happenings in the area; baking bread; cooking and singing at the piano. Of course, the house was never locked day or night or even when we were away. We had no fears other than being wary of snakes and scorpions.

My father couldn’t have been better suited to this isolated part of the country as he was such a zealous person with the most diligent of scruples. His office was the law of the land. He was hands-on administrator, magistrate and legal advisor. With the aid of the local white police officer, his much mutually respected black clerk and the black police sergeants and official interpreter, prosecuted or jailed lawbreakers in a very formal court setting in the government office. Poaching was not too much a problem in those days, but probably most of those in the little jail that held no more than about ten to twenty were men guilty of stealing cattle, goats or donkeys from each other or poaching the occasional Royal Game.

Of course, I was too young to be told about cases of rape, were there to be. I saw in the Botswana archives that two black women were imprisoned for theft in 1953. Illiteracy was never an excuse for poaching. The poaching and the punishment for killing Royal Game, such as roan and sable antelope, eland, giraffe and elephant, provided of course, a more severe penalty. The Royal Game Law was to protect endangered species of the time.

The male prisoners were always sentenced to “hard labour”. Under supervision, they attended to the gardens and grounds of the Government camp and houses. Like my parents, we accepted them as harmless people, smiling and friendly. Some had more taxing hard labour than others. They would, with their spades and pick-axes, clear the bush to form roads quite far afield. Not long after we arrived, bushes and trees were cleared away to make an airstrip about a mile from our house. I was told that the danger of thirst and wild animals was enough of a deterrent to them escaping. In my father’s time, there was no record of an attempt of an escape. It was a known fact that the prisoners were given better food, medical treatment and shelter of a far greater level than they would have had they not offended! So, it was not unknown for them to re-offend for their own comfort.

The black community lived half a mile away near the prison in mud huts, called the location. The huts were thatched, small and round and well insulated against the hot weather and cold winter nights. The black people who were not government employees tended to be illiterate. There were no proper schools for anyone, in the area at that time.

The farmers, mostly Afrikaans-speaking, lived on their vast cattle farms, separated from each other by several hours’ slow journey on the most rudimentary tracks or roads. Ox wagon and donkey cart were still used and no doubt considered more dependable than the trucks that were sorely strained by the heavy sand. Some children were taken to Dekar, the centre-point for the farming community, some ten miles north of Ghanzi. There, children lived as boarders in a large farmhouse. The teacher, Mr Wehye had very little means and the facilities and resources were limited. Teenage boys and girls were sleeping in the same room.

To raise money for a school to be built, a concert was put on at Dekar. I was tasked to perform two songs. My blonde hair had been curled especially for the occasion, resulting in a perfect image of Shirley Temple except for my missing front teeth that the Tooth Fairy paid me a penny for each tooth.

Story and words by Fay Pearson

About Fay Pearson (neé Midgley)

I was born in Johannesburg in March 1943 when my father, Ernest Midgley (1906-1992) was Administration Officer (and District Commissioner) in Bechuanaland Protectorate from 1927-1962. My father and mother (Olga), were stationed in Tsane, Kanye, Tsabong, Lobatsi (1943), Francistown (1947-1950), Ghanzi (1950-1957), Mahalapye (1957- 1958), Machaneng, Tuli Block. When my father retired he lived in Gaborone for two years before moving to Nottingham Road, Natal, South Africa.

My father’s best station was in Ghanzi from 1950-1957 during which time I was aged 7-14. My older brother (Alan) and I went to boarding school in the Cape and Eastern Cape. During our time in Ghanzi, our unaccompanied journeys to school twice a year took us six days each.

I trained as a general nurse at Groote Schuur, Cape Town and I went to the UK to train as a midwife. I met my husband (George) in the UK when he was an Officer in the Royal Navy. We were married in Cape Town in 1967.

George and I now live in Portsmouth (UK) where I actively recount my many vivid memories of the by-gone days of Bechuanaland. I am passionate about my amazing childhood in Bechuanaland Protectorate and really hungry to share my stories.