Botswana elephants – to trophy hunt and cull, or not?

The current international furore over a Botswana government White Paper (discussion document) regarding elephant management necessitates an understanding of the entire picture. This post is one of eight posts from various sources looking at this issue from different angles.

Opinion from Erik Verreynne (pictured right) – livestock and wildlife veterinary surgeon in Botswana

Opinion from Erik Verreynne (pictured right) – livestock and wildlife veterinary surgeon in Botswana

The debate about the proposed lifting of the hunting ban in Botswana continues. It’s not surprising that elephants dominate the debate and that the arguments are based on various perspectives and perceptions. Various solutions are offered and are driven by arguments on lethal versus non-lethal approaches and hunting versus photographic tourism industry sustainability.

What is not acknowledged by many participants, is that this very complex situation is highlighting a very important conundrum facing conservation. The issue is not simply about elephants. The issue is about elephants and people, more precisely wildlife and people. Human presence close to conservation areas and the interfaces it creates, is the most important conservation challenge faced in Africa. The best way to illustrate this conundrum, is to analyse the situation from a holistic perspective.

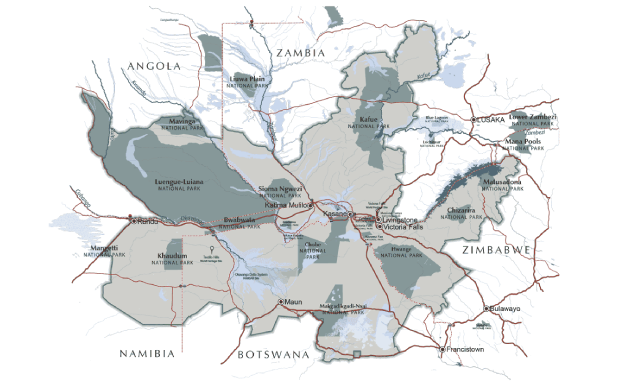

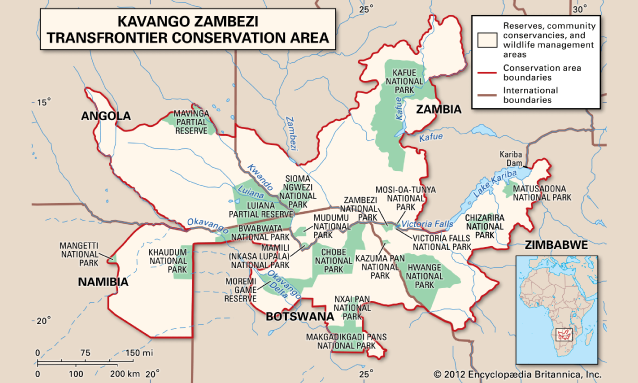

Botswana, with some of its neighbours, is facing unique challenges concerning its wildlife. Nearly 17% of Botswana is under Protected Areas, otherwise known as National Parks and Game Reserves. That is more than the 10% stipulated internationally. Very few of these protected areas have any fences and none are fully fenced, allowing wildlife to come and go. An additional 32% of Botswana is designated as Wildlife Management Areas where people and wildlife co-exist in some form or another.

More than 65% of Botswana’s wildlife occurs outside the Protected Areas, in the Wildlife Management Areas(WMAs). Surrounding these WMAs lies the unprotected pastoral and farming areas. Communities reside along the boundaries of Protected Areas or inside and along many WMA boundaries, where they and their livestock must share the resources with wildlife. Subsistence livestock and crop production are the main sources of livelihoods. The land division in Botswana creates a huge spatial overlap between people and wildlife.

The scale of the demographic human-wildlife interface in Botswana is well illustrated by the elephant issue. The elephant range includes most of the Ngamiland District in the west, all of the Chobe District in the north and parts of the Central District in the east and south.

The elephant range in northern Botswana varies from 85,000 km² during the dry season to more than 116,000 km² during the wet season.

Botswana’s elephant population

Botswana’s elephant population

According to Dr. Mike Chase (Elephants Without Borders, pictured right), the elephant population in Botswana was estimated at between 116,191 and 136,036 during the dry season of 2018. (In the absence of other published population data, I will refer to those survey results). Only about 23,000 km² (about 20%) of the elephant range falls within the Protected Areas, about 70,000 km² (or 65% of the range) in WMAs and forest reserves and the rest of the range covers ranches and pastoral areas.

During the aerial survey in 2018, only 20% of the elephants (about 25,222) were counted in the Protected Areas, 57% of the elephants (nearly 72,000 at an estimated density of 1.4 elephant/km²) were counted in WMAs and forest reserves, and 22% (about 27,750 at an estimated density of 1.2-1.3 elephant/km²) were counted in pastoral areas and on ranches.

The elephants have taken semi-permanent residency in these areas and may only move during the rainy season.

In theory this means that, if elephants and people were evenly spread, there would be a high probability of an elephant within 600m from a person at any given time in the pastoral and farming areas. In reality, both settlements and human activities overlap with elephant concentrations where common resources like water are shared.

Significantly, nearly half of Southern Africa’s elephants were counted during the survey in an area as big as South Carolina or Portugal. From another perspective, more than 5% of the total estimated population of elephants in Africa was counted only in the small section of pastoral areas in Botswana demarcated solely for agricultural use.

Ngamiland District has a population of about 165,000 people (at a density of 1.5 persons/km²) while Chobe district has a population of about 26,000 people at a density of 1.25 person/km². The 2016 Botswana agricultural report indicated a total of 238,132 cattle and 6,876 ha of subsistence crops on 9,072 holdings in Ngamiland. The dry period aerial count report indicates nearly half the cattle population in Ngamiland shares the landscape with elephants at a cattle density of 1.4/km². Almost all subsistence crops farming in Ngamiland falls within the elephant range.

In 1992, the elephant population was estimated at 55,000 – so the current elephant population is more double what it was about twenty seven years ago. At the same time, the human population has increased, and activities expanded. Botswana is now looking after nearly half the Southern African elephant population in an area of less than 100,000 km², and nearly 80% of these elephants share the land with people.

Elephant impact on environment and communities

The drivers for human-wildlife conflict are obvious and the price to pay is hefty. The international perception that Botswana is one big wilderness is skewed and as such creates a skewed expectation about wildlife and people.

With a total human population of less than 2,5 million people, the argument that there are too many people is invalid. The situation clearly illustrates how expectations based on wrong perceptions can drive arguments and solutions. Many do not want to accept there is a crisis in Botswana because they downplay the human component and expect one big game reserve.

The current debate focuses much on numbers and asks whether Botswana has too many elephants. That inevitably leads to the question on limits of Botswana’s international responsibility towards elephant conservation. There is no doubt that elephant numbers internationally are under pressure. There is also no doubt that elephants play an important role in modifying landscapes, and should be conserved.

Acceptable densities of elephants in different landscapes and thresholds for management vary and the impact on vegetation is more important than the numbers. Even though the vegetation impact in certain areas looks severe, the population density in Botswana is within the acceptable limits of 2-3 elephant/km² – the elephant density according to the 2018 survey averages about 1.22 elephant/km² across the range in Botswana.

But again, range and impact can be misleading: Firstly, the range is artificial, as 22% of the elephant range in Botswana is not intended for wildlife. Secondly and more importantly, is the issue of the impact of elephants on the ecology, and ecosystem resilience to recover or change – where the land is subject to differing uses. These issues (elephant impact and ecosystem resilience) differ when people, livestock and elephants share the same landscape.

Impacts where there are spatial overlaps between people, livestock and elephants are likely to be more severe and the ecosystem will recover more slowly. Acceptable density thresholds of elephants in those areas should therefore be less than they are in ecosystems with little or now overlap between people, livestock and elephants.

Furthermore, when acceptable elephant densities are determined, the impacts on people and livelihoods are of paramount importance – yet are being ignored. Management objectives of areas shared by people and livestock also consider human needs and are likely to be less considerate of the long-term ecological benefits that might be brought about by elephant landscape changes. In other words, in these areas there is of necessity a bias towards human needs, and tolerance of elephants is reduced.

Elephant conservation

In a country that has already set aside nearly half of its surface area for some form of wildlife conservation, the levels of crop damage, livestock losses and damage to infrastructure in areas that have been zoned mainly for human use, clearly indicates that the threshold of acceptable damage by wildlife has been exceeded in those areas.

From a pristine ecological perspective, the answer about elephant numbers in Botswana may be that the status quo is acceptable. From a human-wildlife conflict perspective, however, it is safe to conclude that Botswana has too many elephants in some land use areas. Management interventions that aim to decrease the elephant densities in the specific areas and preventing influx into more densely populated areas are therefore justified. That raises another challenge facing Botswana.

The international conservation status of a very charismatic and iconic species dictates the limits of accepted wildlife management practices available to resolve the problem.

Elephant conservation has increased in profile due to rampant poaching, and management options tend to focus on increasing elephant numbers by increasing safety from poaching and avoiding losses. Methods to control populations are accordingly not considered anymore.

Where elephant numbers have dropped significantly in some countries due to the rampant poaching, numbers in Botswana have increased to unacceptable levels in certain land use areas. The human-elephant conflict in Botswana requires a critical evaluation of current elephant conservation measures. The success rate of many of the options are hailed as high, but when measured considering people as part of the landscape the success rate becomes questionable and threatens sustainability of the management activity.

Corridors inside countries and across international borders are a much-promoted solution for natural dispersal of elephants from high density to low density populations. The corridors are established to allow dispersal while avoiding human conflict, and as a result human development has to be reduced in these corridors.

The establishment of the KAZA TFCA to accommodate the redistribution of the estimated 230,000 elephants in five Southern African range states is considered a milestone in elephant conservation.

The establishment of the KAZA TFCA to accommodate the redistribution of the estimated 230,000 elephants in five Southern African range states is considered a milestone in elephant conservation.

Despite media reports of a big influx of elephants into Botswana as a safe haven and movement between Botswana and its northern neighbours, the most recent aerial surveys do not support the expected movement north into the KAZA TFCA.

According to EWB reports, the elephant population has been stable since 2010 and instead of moving north to area of lower densities, elephants in Botswana are moving south and deeper into human populated areas, despite the presence of fences. Does this imply the various range states have reached their saturated densities or does that mean the corridors have been selected incorrectly and are failing?

Whatever the reason, the conundrum faced is that the current solution to Botswana’s elephant problem is currently not working, and an unsustainable number of elephants are sharing the land with people, and Botswana is running out of time.

Reducing elephant numbers

Translocation of elephants is under consideration, but enormous costs involved in relocating large numbers of elephant is likely the reason, despite invitations and donations, that no elephants have been relocated out of Botswana. The number of elephants that would have to be relocated from Botswana to make a difference in areas of conflict with people amounts to many thousands, which would be impractical. As such, the potential benefit of relocation is limited for Botswana, and more beneficial in establishing new populations in previous range states stable enough to control poaching.

The potential use of contraception in elephants in Botswana is also considered, but contraception is a long-term management tool to be used to reduce population growth in smaller populations in selected areas. It will not provide immediate solutions to the current challenges.

That leaves coexistence of humans and wildlife, and the concept of sustainable utilisation. Coexistence remains the most important strategy when the major conservation challenge of lack of new conservation land and increased pressure on existing Protected Areas. Many NGOs in Botswana are doing sterling work in finding ways to promote peaceful coexistence. Coexistence, however, has some limitations because it requires the cooperation of both people and elephants, and the former is value based. Coexistence is determined by “how” and “how much” people can benefit from the coexistence. The elephant crisis in Botswana illustrates the limitation very effectively.

Coexistence in wildlife management areas where most of Botswana’s elephants occur has actually been in place for many years. Although education has resolved some human resistance, the increased number of elephants in recent years has diluted the perceived limited benefits, and reduced community cooperation.

The communities now demand and support the lifting of the hunting ban. For coexistence to be restored in these areas, human resistance has to be reduced, by reducing elephant densities or increasing tangible benefits for the local people.

Tangible benefits through tourism income can provide the lion’s share of benefits, but protein provision and trophy hunting income must be considered to restore lost cooperation.

Tourism-based incentives on their own have proved to be insufficient – partially because thresholds of impact were based on elephant needs and partially because the benefits to communities did not increase as elephant numbers and impacts increased.

Coexistence in pastoral areas and livestock ranches presents the biggest conservation dilemma for Botswana and illustrates the limits of coexistence.

Tourism, hunting and coexisting with elephants

By marketing “wilderness”, we have created an expectation with eco-tourists who do not want to see rural people and livestock while on safari. That excludes a major source of benefit that would promote coexistence in pastoral areas. As result, the priority of coexistence in the pastoral and ranching areas is strongly bias towards protecting people and their livelihoods against elephant damage. In short, local people view their own existence and livelihoods as priority and consider coexistence as unnecessary because localised tangible benefits from elephants are perceived as non-existent. Rather, they demand total protection from elephants, or removal of elephants.

The sheer number of elephants “coexisting” in the affected pastoral areas renders total protection a very difficult and expensive process that becomes difficult to justify from a taxpayer’s perspective. The use of bees, flashing lights and chili pepper in various forms have been trialled with various degrees of success and while it may work in some areas, it did not work in others. Unless we can educate the international tourist that an Africa with people, livestock, crops and wildlife is worth a paying visit, consumptive-based benefits to promote co-existence in pastoral areas will remain the reality.

Where do you draw the line? Elephants will expand their range if allowed to. As witnessed in Botswana, they inevitably reach more developed areas with higher income generating activities. Tourism and hunting do not provide sufficient benefits to promote coexistence, and so a problem-animal control culling program needs to be instigated – to protect people and property. The only way to prevent large scale bloodshed is to prevent elephants from entering these areas. That introduces the option of fences.

Botswana is very aware of the intrinsic value and the international conservation responsibility towards elephant conservation. The growth of the elephant population testifies to that. But the elephant problem faced needs to be acknowledged. While Botswana is accommodating a significant population of elephants in large Protected Areas, most Botswana elephants are outside these protected areas, sharing the land with people at densities that put enormous strain on resources.

Finding solutions

People are part of the equation and should be part of the solution. That includes adapting our management objectives and impact assessment to accommodate the needs and impacts of local communities, which will naturally require limits on densities and dispersal. A common tendency as part of opposing arguments, is to attribute community concerns to manipulation by stakeholder groups, mostly because the opposing stakeholders fear the community concerns may contradict more idealistic solutions.

Another strategy is to blame it on political manipulation. Unfortunately, these tactics do not provide solutions but remove the focus from the real community concerns and limit the painful dissection needed to prevent crisis management from overriding much needed lasting practical solutions.

Resolving the challenges will require a combination of solutions and critical assessment of current approaches. It will require accepting that where people and wildlife are sharing the landscape, the needs of communities are important in wildlife management objectives.

A solution will require an acceptance of the concept of limits and barriers, and that coexistence is value-based and depends on tangible human benefits correlated to sacrifices. It will require acceptance that benefits in some areas cannot be provided by photographic tourism only.

It is therefore justified to consider consumptive-based benefits. It will have to address the contradiction and challenges the unequal distribution of an internationally desired species can cause. After all, Botswana is much more than simply elephants.

About the author:

About the author:

Dr FJ (Erik) Verreynne qualified in 1990 as veterinary surgeon at the Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria. For the past 20 years he has been involved with various aspects of wildlife conservation, immobilisation, management and research in Southern Africa. He has been resident in Botswana since 2002.

He has intensive knowledge of the region, country and its environment. He is registered as veterinary surgeon with The Botswana Veterinary Medical Board, the South African Veterinary Council and The Royal College of Veterinary surgeons. He is a member of the South African Veterinary Association Wildlife Group, member of the technical committee of the Kalahari Conservation Society and member of the Botswana Rhino Management Committee and is registered as a game capture operator in the Republic of Botswana.

He completed a M. Phil. (Wildlife Management)-degree with the University of Pretoria and is busy with an ongoing research project in Updating the Central database for Southern White Rhino (ceratotherium simum) under private ownership in Botswana while investigating the genetic variations in the population to use it as a management tool in a national breeding management approach. He has a keen interest in wildlife disease surveillance and is promoting the establishment of a Centre for Wildlife Disease Surveillance in Botswana.

Source: africageographic.com, vetagric.co.bw