12 July 2023

Newly published Kimberley Process numbers give fresh insights into current market developments.

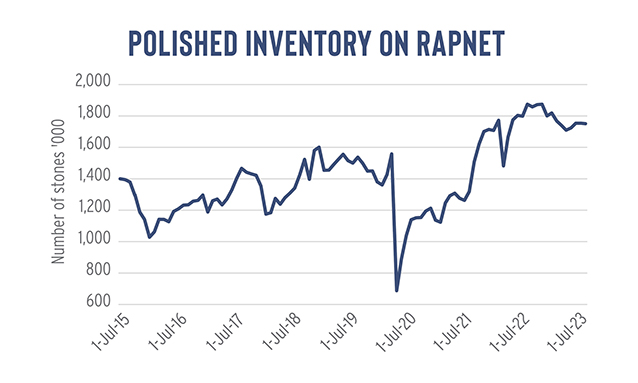

Too many rough diamonds were pushed into the market during the recovery period from COVID-19. The industry enjoyed a strong period in 2021 and the beginning of 2022, and perhaps didn’t foresee the current slowdown. Now, as demand has slowed, polished inventory levels are high. Buoyant rough trading in the past two years has pushed up polished supply at a time when market weakness has set in.

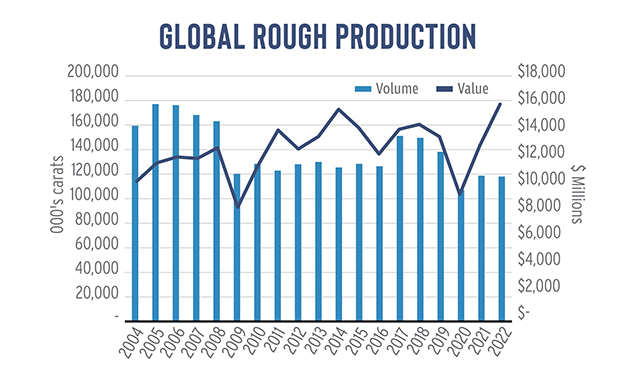

Newly published Kimberley Process (KP) statistics reveal that global rough production was higher than expected in 2022 as Russia remained the dominant supplier despite US sanctions targeting the country’s goods. Global production slid 1% by volume to 118 million carats during the year, while the value of output jumped 24% to $16.02 billion — a record high since the KP began publishing data in 2004 (see Figure 1).

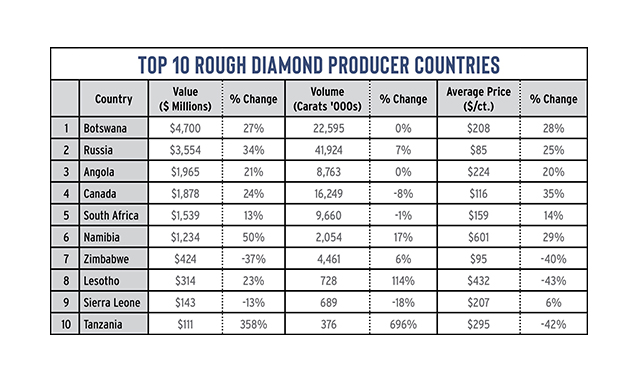

Russia ranked as the largest producer by volume, while Botswana topped the list in value terms, followed by Russia, Angola, Canada, and South Africa (see Figure 2).

The statistics provide important context to current market conditions. Here, below are what three insights the data — or the rough market in 2022 — reveal about the diamond-industry dynamic in 2023.

Supply overhang

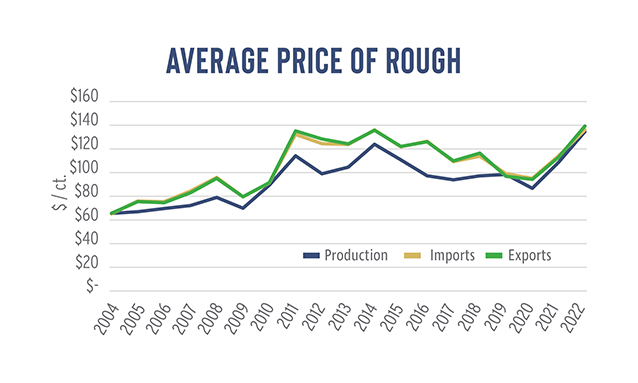

Rough trading slowed in 2022 from the previous year with fewer goods changing hands, but rough prices rose significantly. The average price of production spiked 25% to a record $136 per carat, while that of the imports and exports increased 20% and 24% respectively, the annual KP figures revealed (see Figure 3).

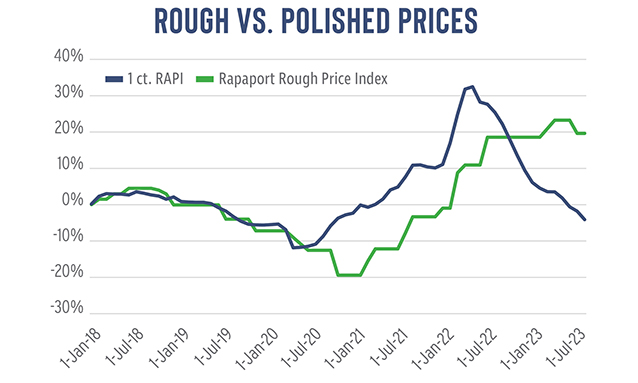

This was in line with an earlier report by De Beers that its average rough price index rose 23% during the year, following an 11% hike in 2021. Rough prices have since come down slightly, although they’re still above 2022 levels despite the slowdown in the diamond market during 2023. Manufacturing profit margins have been squeezed: Rough prices are still high, while polished prices have declined since late March 2022 (see Figure 4). The RapNet Diamond Index (RAPI™) for 1-carat diamonds fell 10.7% for the full year in 2022 and by 8.4% in the first half of 2023.

Rough prices rose as manufacturers had an insatiable desire for goods during the good times of 2021 and the first half of 2022. Large volumes of rough entered the market during that period, even as the polished sector was already slowing down. That has resulted in high polished inventory in 2023. The number of stones on RapNet is still high, with 1.75 million diamonds listed on the site as of July 1, down 7% from a year earlier, but 16% above the pre-COVID-19 levels recorded on July 1, 2019 (see Figure 5).

Manufacturers curbed their rough buying in the first half of this year. De Beers’ rough sales dropped 24% year on year to an estimated $2.42 billion during the six months, while India’s rough imports declined 16% to $6.77 billion in the first five months of the year, according to the latest data from the Gem and Jewellery Export Promotion Council (GJEPC).

The rough market remains cautious going into the second half, largely as manufacturing profit is still tight. Polished suppliers have enough inventory to see them through the next few months. While preparation for the holiday season will likely lift rough sales toward the end of the third quarter, trading is still expected to fall short of 2022 levels. The mining companies are expected to adjust their production programs accordingly.

Russian goods on the market

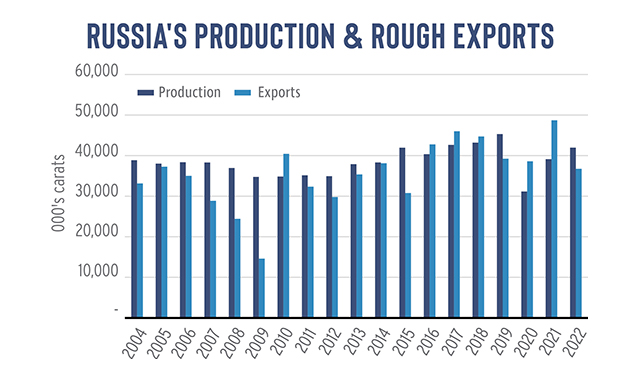

Russia was the wild card in 2022. Whereas it was assumed the sanctions imposed in February by the US on Russian-sourced diamonds would lead to shortages, the goods continued to enter the market — propping up polished inventories.

The country exported 36.7 million carats of rough valued at $3.87 billion during 2022. Some 12.1 million carats were imported to Belgium from Russia and 4.8 million carats to India, according to Rapaport calculations based on government data those countries published. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), which the KP ranked as the largest rough-trading center, was likely another major destination for Russian rough, although Dubai does not disclose the full details of its trade.

The figures highlight one of two scenarios when it comes to Russian rough. First, that there is a market for these diamonds, and manufacturers are entitled to supply those countries provided it is legal for them to do so in their jurisdiction.

Secondly, there is a need to address the issue of “substantial transformation” — a pathway through which the current US sanctions still allow Russian-origin rough diamonds to enter the US if they are cut and polished in a third country, as explained by the Jewelers Vigilance Committee (JVC). The Group of Seven (G7) nations — Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US — are working on measures that will require companies to disclose the origin of their diamond imports, both rough and polished.

Meanwhile, Alrosa, which accounts for the vast majority of Russia’s output, continues to sell, and manufacturers continue to buy from the miner. That said, it seems Alrosa has built up some inventory considering Russia produced 41.9 million carats and exported 36 million worth in 2022 (see Figure 6).

While Alrosa stopped publishing market updates when the war broke out, its rough sales remain a significant unknown factor in the market. It is left to manufacturers buying from the company to be transparent about the source of their supply to ensure they are being siphoned through the proper, legal channels.

Botswana beneficiation

Last year was a significant one for Botswana, as it negotiated a new deal with De Beers to bring added value to its local diamond industry. The delayed agreement was finally signed at the end of June 2023, which entitles the state-owned Okavango Diamond Company (ODC) to eventually receive 50% of De Beers’ local production, among other terms.

Meanwhile, the government also bought a 24% stake in manufacturer HB Botswana, and ODC agreed to supply HB with rough in a value-add deal through which ODC will gain a profit share from the resulting polished.

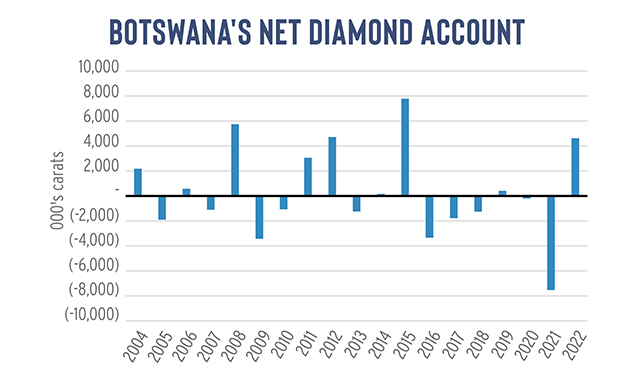

As Botswana sought to improve its beneficiation program, a large volume of goods stayed in the country. Its net diamond account — production plus imports minus exports — came to 4.6 million carats valued at $1.4 billion, whereas it has been a net exporter of rough in the previous six years (see Figure 7).

It is likely that those 4.6 million carats were earmarked for local manufacturing or trading. A small portion may be held by De Beers, which is loath to carry inventory. De Beers’ group production exceeded sales by only 1.2 million carats during 2022, as per parent company Anglo American’s annual report.

Rapaport estimates Okavango sold around 5.9 million carats in 2022, accounting for 17% of Botswana’s production of 22.6 million carats that was reported by the KP. However, ODC was entitled to 25% of that total. The difference between what ODC presumably took as its full allotment and its sales leaves around 2.8 million carats.

Okavango has not disclosed how much of its supply will go to HB. It has also long touted the idea of selling via long-term contracts rather than its tender system, which would give it some protection in a downward trending market. It is likely weighing its options as it gains access to greater supply.

While Botswana starts to implement its agreements with De Beers and HB, more details of those new arrangements will probably be revealed in the next year. Meanwhile, ODC will soon emerge as a major rough supplier, and the parastatal appears to have a bit of inventory as a buffer, or perhaps that it can use to set the new mechanisms in motion.

Conclusion

The KP data is important as it is a succinct summary of the condition of the rough market in different locations. Each country among the major producers, manufacturing and trading centers warrants analysis, and there are many issues that have not been addressed here.

The three topics outlined in this feature — excess supply, Russia and Botswana — are having the greatest impact on the market currently. The 2022 KP data highlights their ongoing influence.

Russia and Botswana demand attention for different reasons, as their rough supply mechanisms not only adapt to evolving market conditions but shape them too. Mostly, they highlight the impact De Beers, Alrosa, and soon Okavango too, exert on the market — even as Russia and Botswana face changing realities.

This article first appeared in the July edition of the Rapaport Research Report. Subscribe here.

Source: https://rapaport.com/analysis/a-rough-overhaul-russia-botswana-and-excess-supply/