There were many other challenges to living in Maun, probably best summed up by the neighbour who came around with a pot of tea for mum while we were moving in and said,

“Tell me what you have forgotten to bring, and I will tell you how to manage without it.”

It was that sort of existence.

There were no significant retail centres in Maun, just a single shop where basic provisions could be obtained and Riley’s hotel and garage. The main supply of provisions was a weekly truck from Francistown that would bring fresh, if somewhat bruised fresh provisions, the mail and the previous week’s newspapers. Clothing was either made by mum or ordered from South Africa; she was happy making the girl’s dresses but found boy’s shorts a bit of a challenge, so these tended to be ordered.

Shoes were a particular challenge (when we wore them, which was not very often), and mum’s solution was to stand us on a piece of paper, trace around our feet and mail the imprint to South Africa for shoes to be ‘fitted’.

We had a vegetable patch in the garden and kept chickens for eggs and Sunday lunch, while trying to keep the snakes out of the chicken coop. Bread was always freshly made by Agnes; every day the bread tins would be put out in the sun, so the dough would rise. Chocolate was a seasonal food; due to the heat of the summer and non-existence of refrigerated lorries, chocolate could only be delivered in solid form during the winter months; hard-boiled sweets were the order of the day in the summer.

The electric supply system was in its infancy. There was a generator that would operate for a few hours each evening, provided there was fuel and the machine was working. We always kept a good supply of gas lamps, paraffin lamps and candles for those evenings when there was no electricity. Needless to say, there was no air-conditioning, although a fan was most effective.

Fridges were either paraffin fuelled, or a charcoal box hung in the tree outside with a bucket of water above. The bucket had a small hole in its bottom, which allowed water to drip onto the charcoal box below, the evaporation keeping the contents cool.

Similar technology was used for our house; a tray of water placed on the lounge floor helped cool the house a bit. We cooked on a wood-fired AGA stove, which kept the house nice and warm in the winter. Hot water was obtained from a wood-fired boiler outside the house; this was generally fired up in the late afternoon, so we had hot water to wash with in the evenings. Timber was an accepted energy source those days; this is before the impact on the environment was fully understood. The timber we used was very hardwood, usually ironwood, which made wonderful coals, but was extremely difficult to chop into suitably sized logs.

Mosquitos were a constant nuisance, particularly in the summer evenings. To try and control the bites, not only would we put repellant on and take tablets, but we would sleep in a fine mesh tent that was moderately effective in keeping the mosquitos out and very effective in keeping any cooling evening breeze out. But very effective sauna’s.

The adults would supplement their protection drinking tonic water (the quinine help combat malaria), flavoured with a bit of gin to temper the bitterness of the quinine. If any of us developed a temperature, and most of us did, we were immediately treated for malaria while the doctor investigated whether there were any other issues. Unfortunately for my younger sister, she got bitten immediately before we left on ‘home’ leave and she developed malaria on the mail boat going to England. The ship doctor didn’t recognize the disease and treated her for flu initially before they realized what the problem was. It took a long time for her to recover, and she still suffers from various after-effects.

A ‘Sunday School’ was run every Sunday by the local missionaries on an inter-denominational basis for the children in the area. We remember arriving one Sunday morning to find a long snake lying along the garden path; fortunately, it had been seen and shot before we arrived. It was then disposed of by incineration in the hot water boiler.

Christmas was always an exciting and eventful time. Invariably there would be a letter from Father Christmas with one’s presents. The letter was always an apology from him that the elves had been very busy, and the orders from Bechuanaland arrived a bit late – the post was not very reliable – and unfortunately, the elves hadn’t finished making and packing the presents, but they would be delivered as soon as possible. And there was also concern that the lions may misbehave themselves with the reindeer, although we were reassured that the trackers and hunters would ‘keep an eye on them’.

Easter also presented its challenge’s. Our grandparents in the UK would always send us some chocolate Easter eggs to celebrate with. Delivery of these presented the Easter Bunny with numerous insurmountable challenges, not the least of which was the legendary Francistown to Maun highway. What arrived after a ship journey to Africa, train to Bechuanaland and finally on the back of a lorry to Maun was barely recognisable as chocolate, let alone an egg shape. Invariably shattered into small pieces and melted down into a shapeless mass. Mum would look at the packaging that survived and using her knowledge of what was generally on sale in England, would ‘help’ us write a thank-you letter to Grandad for the lovely Easter egg which we thoroughly enjoyed eating! Anything else may have upset Grandad, apparently.

There was a small hospital in Maun which provided a basic level of care. If anything more sophisticated was required, it was necessary to travel to either South Africa or Rhodesia. I don’t have fond memories of the hospital, as they extracted my milk teeth under general anaesthetic; there being no dentist in Maun. General anaesthetic was administered as gas; it was a foul-smelling substance. My mum subsequently told me that it was touch and go who was anaesthetised, me or the 4 adults restraining me! The window and door were kept open for ventilation while the gas was administered to me. The police subsequently, following an unusually large number of deaths under general anaesthetic, found that one of the doctors practising at the hospital had forged his medical certificates. I understand that he was successfully prosecuted.

We returned to the UK every 3 years on ‘home’ leave. These were very exciting trips; initially, we would travel on the regular mail-boat service between the UK and South Africa, but for our final trip in 1966 my sister and I flew from Johannesburg to London via Nairobi and Rome at the end of our boarding school term (she was 10, I was 9 years old, and the air-hostesses treated us like royalty) to meet up with our parents and siblings. These trips also brought out the differences in culture, often in an amusing way. In one instance one Christmas, while visiting our family in Yorkshire, my parents decided to stop and buy some traditional fish-and-chips for dinner. It was winter, and there was snow on the roads.

My sister and I were reluctant to wear more than our shorts and shirts, so we were left in the van while mum and dad went to buy the fish-and-chips. After a while, we got bored so hopped out of the van and walked barefoot through the snow across the tarmac into the shop to investigate the delay. Mum and Dad were very embarrassed when they saw us and pretended not to know us, but that soon changed when we walked up to them. Mum said we looked like street urchins! On another trip, my sister and I were taken to a large department store in England for the first time and we were fascinated by the escalators.

Apparently, we were quite happy spending our time riding up and down the escalators rather than shopping. This is also the time when Teflon coated frying pans (the Teflon coating being black) became available, so mum bought one to take back to Bechuanaland. Without thinking she left it in the kitchen. Agnes saw this and assumed mum’s cooking had not gone quite to plan, so took the frying pan outside and cleaned it with a bit of best Kalahari sand. She came back with a huge smile on her face to show mum her nice clean frying pan with not a speck of black Teflon visible! Mum accepted the blame for this.

As a child, the one toy I cherished above all others was a steerable, wire-framed car with wheels made of used Nugget shoe polish tins that the local children played with. There is nothing that would have given me more pleasure than to add one of these to my toy car collection.

But for whatever reason, my parents would not buy one for me. I thought I had solved the problem one day when at a local market I traded a leather football my grandfather had sent me from England for a wire-framed car, only for my parents to instantly reverse the trade. I do not know why they did this, but the result was two unhappy little boys.

Immediately before independence, Chief Moremi had decided that part of the Swamps should be preserved as a nature reserve for the future, so his descendants could see and enjoy the wildlife. He needed funds to initiate this project, so he approached the residents of Maun for a financial contribution. I am pleased that my parents contributed to this initiative and take great pleasure in visiting the park when in Maun. I also enjoyed a bit of banter with the park attendants when asked to pay my entry fee (which I always do). And it is credit to Chief Moremi for having the foresight and determination to deliver his dream, not for his people but also his country and the many tourists that enjoy viewing the wild animals.

School education in Maun was limited; there was a primary school that we attended for the first 3 years. The school had one classroom and one teacher. It was great fun to be there, as we all knew each other and were friends. After three years we all went to boarding school, generally in South Africa. In our case, my parents had no network in South Africa, and it was effectively a foreign country for us. We were both sent at the age of 8 initially to Capricorn in Pietersburg, in the then Northern Transvaal. This school provided education for many children from northern countries, including Bechuanaland.

I remember my elder sister going first, leaving me feeling lost at home as she was my friend and playmate. The boarding schools were strict in those days, and we were not allowed to bring any books or toys with us and comics were not allowed to be mailed to us, only letters. And in those days, one attended school for the full term, and travelled during the school holiday, not the other way around. Phone calls to talk to mum and dad were not possible.

I went the following year and was excited at the prospect of being reunited with my sister, but I was not prepared for what lay ahead. It subsequently turned out that part of this was due to mum’s own emotional difficulty in sending her children away knowing she wouldn’t see us until end of term in about 10 weeks; she explained to my wife many years later that the only way she could control her emotions was to walk us into our dormitory, unpack our suitcase, say good-bye (no kisses or hugs), turnaround and walk straight out. She didn’t want her children to see her distressed.

On the other side of the fence, it felt like abandonment, and to make matters worse, the dormitory for my year group was full, so I got put in with the boy’s the next year up; at times I was no more than a punch-bag. I was terribly homesick, so the next day I sought out my sister in the playground, only to get caned for crossing a demarcation line keeping boys and girls separate. A further difficulty surrounded food; there was a ‘tuck box’ facility where one could bring some treats from home for the week to eat in the afternoon, which worked well for the weekly boarders but for those of us who were termly boarders, we went without as we could not keep food fresh for the duration.

I returned at the end of the first term covered in septic sores, and was taken straight to Mahalapye hospital, where the doctor diagnosed the onset of scurvy and prescribed fresh fruit and vegetables, with some multi-vitamin tablets; the school food was simply not good. For the rest of the year, mum would send me a bit of pocket money each week (having understood the letter rules) to buy myself a piece of fruit each weekend, which I did. To this day I am a regular eater of fresh fruit and vegetables, so maybe some good came of this, although I am still missing a small bit of the top of my ear.

Communications with home were limited to letters, the phone system being limited, expensive and in its infancy and certainly not available to pupils. Unfortunately, my mum fell foul of the ‘no comics’ rule by sending me a weekly roll containing the magazine ‘Look and Learn’ which I enjoyed and a letter. On arrival at the school, the roll was looked at, classified as a comic and thrown into the bin, with nothing being said to me. Towards the end of the term, one of our Bechuanaland friends was in the area and visited the boarding school; I asked him to give my mother a telling off when he saw her for not writing to me. Mum was absolutely mortified about this.

Written by Ian Brooks

Ian is Donald Brooks’ son. His father arrived in Maun in early 1962, leaving four years later in 1966. He was a police officer, trained in the UK, but working in the Colonial Service. His brief on being transferred to Maun was to sort out the ‘w’ element; there was a perception that there was insufficient regulation, particularly the hunting of the wild animals, and his task was to bring this under control.

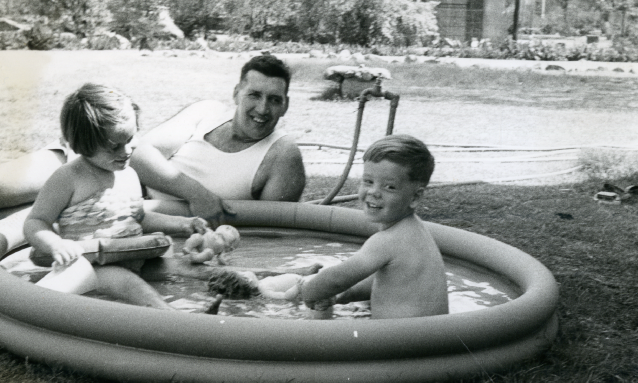

Ian and his siblings were children while in Bechuanaland Protectorate/ Botswana; the younger 3 children were born in Bechuanaland Protectorate. The context is a combination of his own memory of life in Maun as a child, as well as various conversations with his parents over the years about the photographs and life in Botswana while they were there (1958 to 1968).

On an overland backpacking trip from Ireland to Cape Town I arrived in Maun in 1970 on a game-viewing flight from Chobe. There I was befriended by Freckie Braithwaite who invited me to stay at his house.

Does anyone have any information on him? Please see my contact email below.

I lived in the Protectorate/Botswana from 1950 – 1969 and in Maun from 1961 – 1968. At that time there were certainly two stores in Maun, Rileys and the NTC (Ngamiland Trading Corporation). The stretch of sand between the mission house, where I lived, and the NTC was one of the most wicked you could experience anywhere in Maun.

I grew up in Zambia and also remember the embarrassment of my English family when I spent my first half term with them. I went barefoot with my cousin to play in the village – to the horror of my aunt who explained that in England children wore shoes!

Look and Learn was a staple in our childhood – our family won a national television quiz on account of our excellent general knowledge.

Happy days!