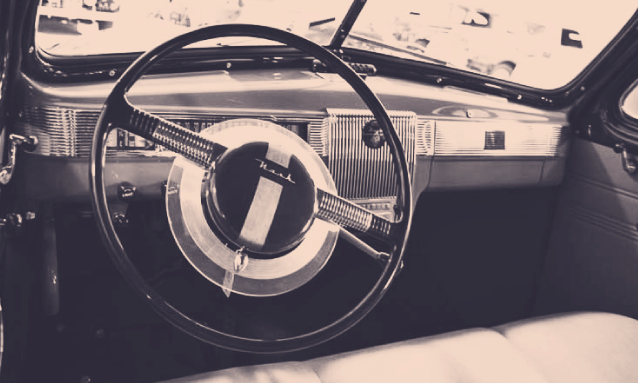

We were all so excited at our lovely new car, the blue Nash Ambassador. It cost £641. The number plate was BPA 72. The ‘A’ stood for Francistown, which was the largest and northern-most town in Bechuanaland Protectorate, on the rail route to Rhodesia.

It really was very clever how the four of us could bed down in this swanky sleeping-model car. Alan was to sleep along the single front bench seat, his feet at the steering wheel end. The main seat in the back of the car was yanked forward to meet the backrests of the front seat, now covering the foot-well. Then the backrest in the rear hitched up to form a bunk for me. The barrier that divided the boot of the car from the back of the seats flapped down to meet the space that the forward lying seat had left, providing a double bed for our parents who slept with their feet in the boot. Get it? A four-berth car!

The arrival of the new car coincided with our return from The Rand (as the area of Johannesburg was called) to Bechuanaland Protectorate and the exciting visit to Francistown of the Royal Family. The Royal family were to meet the locals on the white, parched grassy aerodrome; a spacious and clear area that could cope with all the crowds.

The big event set the town and country in a spin. Frocks were hastily run up on sewing machines or those with money, ordered through John Orr’s catalogue from Johannesburg. Hats and gloves for the ladies were, of course, de rigueur.

My father’s Royal Naval training believed that only he could be trusted to wield the shoe whitener for his shoes and pith helmet to complete his white District Administrator’s uniform with its mandarin collar, long trousers and sword. Certainly not a servant or even my mother.

“Don’t let her loose, now!” Mummy warned the teacher in charge.

“Knowing her, she is bound to dash up to the king, leap onto his lap and make a fool of us!”

“How did Mummy know I would do that?” I wondered looking at the king seated far away in his canopied rostrum receiving the notable locals who were presented to him, one at a time.

After a long, long time of waiting, the queen approached.

“The queen is coming! The queen is coming!” I yelled, jumping up and down.

“Ssssh!” The schoolteacher tapped me on the shoulder. I poked my fingers into the smocking in the front of my green viyella dress Mrs Ciring had sent me the day that Alan posed as Pinkie.

I saw the queen look at me. She looked at me!

“Hello, Queen!” I called out, leaping forward. The two princesses behind her laughed. The queen gently angled her head sideways and said,

“Hello, little one.”

I was yanked back into line. When the queen had moved on, the teacher looked angry,

“You shouldn’t have called her that!”

“Why not, she is the queen, isn’t she?’

As the school children dispersed, Alan realised that our parents would no longer have a marker as to where we were. He took charge and guided me to our lovely new (unlocked) car where we waited and waited and waited. When our parents found us, they were so proud of Alan’s common sense and spoke about it for years to come.

Francistown was a busy little hick dorp, due to the presence of some of what was then modestly productive gold and diamonds mines nearby. The population of white people would have been less than a hundred or so. Even as I child, had me sense it to be a place in which gossip, cattiness, warmth and friendship boiled and bubbled in the goldfish bowl of the white community. Little would we consider for a moment that it could have been likewise for the black community who, although ‘invisible’ will have observed and heard our antics and will have even had antics of their own. No never!

My family had to endure constant moves. We had also lived in Francistown previously around the time of my birth. We had also been posted to Serowe, Lobatsi as well as Tsabong in the south and even Tsane, a real outback station in the Kalahari. Because he was so junior, my father could be sent at very short notice, to cover for other District Commissioners who were on leave or off-sick.

The tall, sweet-scented mauve flowering Syringa trees dappled their shade on the white-washed administrative offices. All the sandy paths and the road around the Government compound were marked out with whitewashed stones the size of footballs. These government offices for the police, clerks, veterinary and stock inspectors, including the District Commissioner, were scattered around a large smooth sandy clearing that was swept daily with leafy branches by a woman, with baby nodding to her motion on her back. It was wrapped tightly to her torso by a thick, grubby blanket.

Outside the main office, an impeccably dressed black policeman in khaki hoisted the Union flag on the dot of 8 o’clock each morning. His gleaming brown boots caught a sparkle from the sun as he clicked his heels as he snapped a salute. His large khaki hat was pinned up on the one side by the imperial badge.

My father’s office dealt with all aspects with the administration of the area including the busy magistrate’s courts as well as meeting everyone, including farmers, traders tribal chiefs and school teachers and no doubt, much more. As a local representative of the government, district commissioners co-ordinated with all the people (black and white), resolving and settling the development and activities of the whole district. There had been a policy of leaving the chiefs to govern their tribal territories with little interference from the Protectorate Government.

The DCs attended a Khotla, (meeting point) in their villages to meet chiefs, African headmen and any of their people who were interested. These meetings were intended to meet their requests and desires, as well as to negotiate any differences connected with local law; always, of course, reporting to head office in Mafeking who then reported to the Home Office in London. It was all highly diplomatic. Of course, all that would have been over the top of my little head, but for you to understand the setting, I feel it completes the picture.

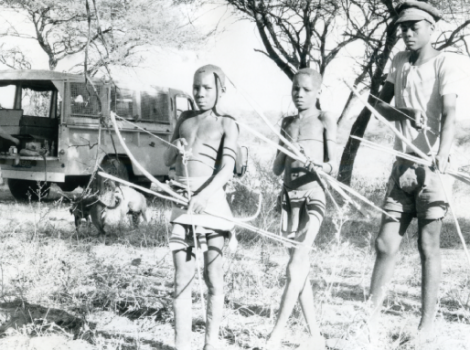

The town had a hotel for white people and a small government hospital that tended to all races. Alan and I attended a large school for about some fifty white children. There were just a handful of shops along the one main street, always bustling, crowded trading stores with a heady mix of stench from animal skins, roughly ground corn, tea, coffee, biltong and the sweat from unwashed people sweating cheerfully and odorously in the 40°C heat. The animal skins that arrived in a state of crude preservation, added to the stench. As much fat as possible had been manually stripped off the animal with knife-scrapings and then it was stretched out, pinned as stiffly as possible, and set out on the ground in the strong dry sunshine with wooden stakes in the ground. The spread-eagled skin was then sprinkled with coarse salt on the raw skin that worked as a germicidal. These dried out skins were brought to the trading stores as stiff, hairy cartoon-like cut-outs of the animals. Our family had jackal karosses that were tanned into soft and cuddly bed-covers, much needed in the winter when nights were quite chilly.

Many Batswana had little farms with cattle and chickens and goats, ears of maize, (corn) which had dried, papery leaves containing large beads of multi-coloured kernels of pink, purple, blue and yellow. They came to buy or sell bags of sorghum wheat; we called “Kaffir Corn”, which in those days had not the slightest derogatory connotation. The black people made Kaffir beer from this corn after it had fermented. The Kaffir-corn made my favourite porridge was a pale brown colour. We called it Ma’bella from its trade name: Maltabela. I ate it piping hot with milk and golden brown Demerara sugar and sometimes a dollop of butter that oozed and melted with an oily aroma.

Regardless of the weather, black babies were bound so tightly in large grubby shawls or blankets to their mothers’ backs that only their heads were free to loll about as flies in their scores attached themselves to the corners of their eyes as they came to buy mealie-meel (ground corn), beads and dress materials. I often wondered how the babies showed no instinct to remove the tickle from the flies on their faces.

Our house in Francistown was in the Government Compound down a wide dusty road. The metal gate made of tubular steel was left open too often even in spite of Daddy’s noisy protestations. Wandering goats also had a way of prising the gate open themselves. Ours was the last house of about ten, at the foot of the road. All the houses were similarly designed with silver-painted corrugated iron roofs to deflect the sub-tropical heat. They all were single storied, with three bedrooms. The yard around the house was spacious with a small lawn in the front of the house.

The sitting room had dark, oak, polished wooden floors. We lit the fireplace for the short season of chilly winter evenings. The dining room had a hatch through to the kitchen, which we never used. The bathroom, with bath and washbasin, had hot and cold running water that came from a boiler in the back yard. The boiler was heated by wood fires lit in the early dawn by the prisoners at the time they also emptied the lavatory bucket from a flap at the back of the building. Although the lavatory was attached to the house, its door was outside, at the back of the house. All the Government officers’ houses all had servants quarters in the grounds of the spacious yards at the back, designed to house up to two Africans; but wives, girlfriends, cousins and their children took advantage without any protestation from my parents.

“They are not doing any harm”, my mother said. “At least they are not a noisy lot. Here, take them this loaf of bread. But don’t you stay there with them. You must respect their privacy and know your place”.

The front of our house was ablaze with hardy poinsettias, the bright red pointed leaves one associates with Christmas cards in England. I delighted in snapping a stem and watching the sticky white milk ooze from the break in the plant. Alan had shown me that. He told me if I tasted the milk I would die. I did taste the milk, but I didn’t die. The lasting horrid bitter taste stuck on my tongue forever. I never did that again.

Beyond the Government offices and at the base of the large kopje, was the government hospital. The policeman’s wife, Mrs Webb was the Nursing sister in charge. Dr Morgan was a tall dark-haired man who looked like Abraham Lincoln without the beard. He was a kind and softly-spoken man with eyes that readily held one’s attention.

I don’t remember ever climbing the kopje. The view from the top will have been memorable, as it would have been the only vantage point to look down beyond the Tati River onto the little town and out over the flat, bush country that was scattered with grass-roofed mud huts. For a little girl my size, the kopje would not have been too difficult a climb. It was only about a mile or two in circumference; but there was a fear of snakes and leopards lurking in the tufts of long yellow grass stuck out from between the red craggy rocks.

Dr Morgan at the little hospital remembered me well from my infancy. I am told that I only weighed ten pounds when I was 6 months old. (It is not unusual for a baby to be born at ten pounds in weight). Dr Morgan had set my mother right by advising her that my milk feeds, served in a lemonade bottle, were far too rich in milk powder. Due to the war, the conventional banana-shaped babies’ bottles were hard to obtain. She realised that adding more powder, I was satisfied for longer; so she did not have to feed or attend to me that often. The downside resulted in constipation that she also reported to him.

This visit to Dr Morgan was different.

“Fay has swallowed a whistle,” my mother worriedly announced to Dr Morgan.

I was seated on his knee as Dr Morgan drew an oblong and a circle to ascertain what shape of whistle I had swallowed.

“The round one, the one that you put in front of your teeth and blow in and out,” I explained.

But he didn’t seem to understand me, as he kept pointing to the long whistle. I was given no treatment, but I was not allowed to go to the regular lavatory that had the bucket of strong smelling white liquid in the bottom which the prisoners removed at 5 in the morning. I had to use the potty until the whistle was found.

It was a very, very hot day, and the dry, powdery light brown, thick sand became cooler under foot, the deeper I dug my bare feet.

“It is funny how the sand is thick here at the front yard, compared with the side of the house where it is hard caked and even a darker brown,” I thought. I wonder if it would be better to die of heat or cold, I wondered to myself?

Alan, who always knew everything, told me that very cold makes you sleepy- but so does heat, I thought. I really didn’t have such an enquiring mind, so I decided to shelve the problem until another time. The newly made lavatory seat provided me with some off-cuts of wood. I pushed them through the sand. They made a 2-inch wide track in the thick sand. Copy Cat. I had seen Alan do that with them. My play was interrupted by Alan’s call just as he appeared around the corner clad in a pair of khaki shorts. His short hair was bleached nearly white from the sunshine with a marked contrast against his sun-tanned body. He was seven.

“C’mon! Let’s swim! Mummy said so!” He pulled his khaki shorts off, revealing his white underpants as I tugged at my cotton dress, leaving on my navy blue cotton bloomers that my mother had made.

It wasn’t really a swimming pool at the side of the house. Maybe some previous District Commissioner had built it as a fishpond. It was about 8 feet oblong, by 5 feet wide and the bricks had been finished crudely with cement. It sloped to the deep end in the middle, which was only about waist high to me, as a 5-year-old. The water was green with algae and very dirty, but we didn’t mind. We still opened our eyes in the water. It was more fun and better tasting after the prisoners had cleaned the pool and filled it with sparkling water so clear we could see our feet.

We played at who could stay under the water the longest, then shrieked with giggles as we took turns on a small black inflated rubber inner tube from a wheelbarrow. We yelled with delight when our favourite gaol-guard walked past.

“Hey, “Tla-kwano”, (come here), Gaol-guard!”

It was our intention to splash him. He was a tall African, proud of his khaki hat, his tired sweat-stained short-sleeved khaki shirt may have been ill-fitting, but he was proud of his position. Protecting his large gun from the splashes, he laughed, revealing a gap from a lost front tooth, shaking his head with amusement at the malaudi’s white-haired children. He went on his way to check that the four prisoners were coping with their various “hard labour” duties, such as watering the garden, weeding and cutting the lawn with hand shears as they hopped on their haunches.

These prisoners did their penance for crimes such as killing antelope out of the shooting season, or stealing cattle or assaulting their friend after too much kaffir beer in their village. We never had any fear of them; we simply kept our distances from each other, due to the language barrier; but we remained friendly with the gaol-guard, who had more English than the few Tswana words we knew. My father would have been responsible for having sentenced these prisoners, but I later learned they felt no animosity for this time of comparative leisure, good food and shelter in the gaol. The Africans in Bechuanaland Protectorate were always especially peaceful and good-natured people.

After a while, Alan had had enough in the water.

“Let’s go inside! Tea time!” He leapt out of the pool.

Our wet feet picked up the loose sand as we ran around the front of the house, up the red shiny concrete steps and stood on the stoep. We paused to check on the progress of the chameleons on the gauze netting which enclosed the stoep. At my mother’s request, the prisoners had handed the reptiles in to her, for the amusement and interest to us children. The chameleon was a big chap. (At least, we had presumed he was male). His body was about seven to eight inches long, with a tail that tapered to a thin prehensile coil that would have stretched out equally as long. We watched the grey, mottled reptile slowly, tentatively and jerkily make its way along, its tiny claws gripping into the minute holes in the metal gauze netting, as its protruding eyes roved in different directions from each other as it looked out for danger.

“I wish I could see it catching a fly!” I said as I carefully extended my fingers under its feet to pick him up.

“Maybe they’ve eaten them all,” Alan decided, glancing round the stoep.

The other two, smaller chameleons were too high and out of reach. The chameleon opened its mouth and made a threatening, quiet, blowing sound, which we knew, was as dangerous as it could get.

“He said haaa at me Alan!” I exclaimed in a shrill voice. I breathed a loud “haaa!” back at the chameleon.

“Let’s make it change colour!” I placed him on the red cushion on one of the big wooden chairs on the stoep and waited. In a minute, he gradually turned from a dull grey to a dull brown.

“It won’t work!”

“Ag come on man!” said Alan impatiently;

“He’ll never go that colour red. Anyway, he’ll fall off the chair; there’s nothing for him to grip. Put him back on the netting, man.”

We went into the lounge and slumped down in separate chairs. My mother strode in to the lounge.

“We must let those chameleons back out into the garden, tomorrow. There are not enough insects indoors for them.” We can always get other ones another time.

Her expression changed, seeing us sitting in the lounge in wet underpants.

“Oh, go and change your broeks! They are wetting the sofa! You can’t stay in wet broeks all day. You know Isaac shouldn’t see you with so few clothes on”.

I was not yet used to Isaac’s presence. He only came to work for us a few weeks previously as houseboy and kitchen helper. I could not think why it should matter if he saw me in my pants. The picanins were clad a lot less than I was then and besides, Alan was as bare as I was! She responded to my sulky retort.

“White girls should not be seen as bare as that! You have to learn to have a sense of decorum. Now go and put your dress on, then you can have tea. Quickly now! Daddy is coming home early tonight to go to a rehearsal.”

I wondered what decorum was. I knew what sense I had. Alan and I changed our clothes. We had left the clothes we had discarded at the swimming pool, but found more clothes in our respective bedrooms and returned to wolf down a slice of fruitcake and a cup of sweet milky tea that Isaac had brought in on a large tray. Daddy was to be rehearsing that evening for the play-reading of “The Importance of being Ernest” in the town hall. That being Daddy’s first name, it was inevitable he was given the part. I never saw these plays as they were always after our bedtime.

I ran up to kiss him hello, smelling the sweet smell of his smooth-shaven firm slightly rounded face. I remember that smell so well. It was from “Prep” shaving cream that came in a jar. Its blue lid boasted of many uses, among which was recommended for insect bites, cuts and bruises. I clung onto his bare, hairy leg below the level of his wide-legged khaki shorts until I was gently but firmly pushed aside as he sat down for his tea, and started “grown-ups” talk with my mother. I went off to play with my dolls.

I ran into the lounge where my parents were talking.

“May I go and play with Jane, Mummy?”

They looked grave and explained to me that Dr Morgan had just diagnosed the young Joubert boy as having Polio. The play-reading was cancelled. Anyone who had been in close contact with the Jouberts in the previous ten days had to keep apart from the rest of the community for the next month. As we had visited them only the previous Sunday, we too, had to go into quarantine.

“Never mind!” My mother searched for the bright side; yet, she knew how difficult an isolated life would be in such a small community

“You at least have Alan to play with! Tomorrow we will go to the Shashi River for a picnic! Won’t that be grand?”

I was trying to understand what a month’s quarantine was going to be like. My concept of time was limited. It seemed like a lifetime. I went into a great big sulk and pouted. It was going to be terrible only playing with Alan for a month!

Bobby hopped down from the top of the cupboard where he had been sleeping. He was an astonishingly tame bushbaby or nag-apie (night ape, as the Afrikaans people called the little furry animal). We were the only folk to have a bush baby as a pet in our community.

He loved being stroked and handled but during the day we were not allowed to handle him as he usually slept all day. In the evening, my mother let him out the window in the front room and he returned in the early hours of the morning from his night out in the bush.

When he slept in his dark corner, he curled himself up into the size smaller than a tennis ball. His mottled grey fur was very soft. He looked into my face with his immense rich brown eyes with pupils as black vertical slashes, as I held him in my cupped hand.

His large, hairless ears were folded lengthways, close to his small round head, but on hearing Alan enter the room, the bare ears darted up to attention. His long prehensile bushy tail rested the length of my arm. I could feel his hind legs tensing preparing himself to jump. We called him Bobby, not after Daddy’s brother who died in the war, but because of the way he jumped. He bobbed around the room. His strong fingers took hold of a piece of apple in his forepaws, and he nibbled hungrily, scattering rejected pips and pith on the lounge carpet. All his fingers and toes had nails except the second on his hind foot, which was clawed. He took a long leap with the apple in his one hand and landed on Alan’s shoulder. He saw that Alan had some raisins in his hand, which was his favourite treat.

Around that time, we acquired another pet: Jacko. He was a Blue Vervet Monkey, brought to us by some Motswana children, as a tiny helpless baby monkey. My mother could not have refused him refuge and gave them a ticky and some sweets. She knew he was so tiny that he needed bottle-feeding.

Daddy was livid when Jacko, was found to be in the house.

“Oh really, Olga. You know that you won’t tame these animals. They are not the same when they grow up!”

He shouted and ranted. Alan and I hid, but remained within ear-shot so that we could learn what would happen to Jacko. We kept the ape, but Daddy won the argument that we would never be able to really domesticate him. In a short time, he proved that by his destructiveness, tearing any paper to shreds. He leapt around the house at speed, knocking precious things over and busied himself to break apart anything he could find, pooing and peeing whenever. When we tried to extract things from him he threateningly showed his teeth and started to bite. The adult monkey is about 15 inches high, grey coat, a very blue coloured tummy, and a long grey tail.

Rather than have the vet put him to sleep, we set up a large thick high pole in the yard at the side of the house, with a box on the top in which he could sleep in safety from any dogs, snakes or other predators. He was tied to this pole by a long thin rope that was tied round his waist. We gave him lots of toys to play with and we think he was happy. This was the only pet in we ever kept in captivity. But had we let Jacko loose in the wild, he would have been a real pest by returning and visiting peoples’ houses and huts. Certainly, he would not have survived as long in the wild.

Still thrilled with the novelty of our new car, the promise of the picnic at the Shashi River was foremost in our minds. Mummy filled the car with picnic food and two thick karosses to lie on. She forgot nothing this time and the car was laden with everything for “just in case we have a breakdown”. Gerry cans with extra water, petrol, letter-writing, watercolours and “skoff” which was bread and jam and a cold chicken, some oranges and some fruit cake; orange squash (Oros) and coffee in a flask.

Driving out of our front yard, we passed our neighbour and gave her a wave. Her husband was the Veterinary officer.

“Come round later for tea” she called out.

“Sorry, we can’t! Polio isolation!” Daddy had a high pitch when he yelled.

Word had travelled fast. She knew what he meant. We passed the government offices and along the railway track. We watched the daily passenger train on the way to Rhodesia clank past slowly as it headed in the direction of Rhodesia. Some African passengers on the train exchanged waves with us.

We waited for the train to continue on its way. The level crossing was on a steep bank. There, of course, were no barriers for so few trains, which is why the train was going so slowly through the edge of town. Once the train was on its way, we set off to cross the line. Just as we were level on the railway line, the car stalled and we glanced up to realise that the train was shunting in reverse towards us! My mother extended her arm out the window.

“Go back! Go Back!” she screamed.

There was no guard on duty at the rear of the train. Daddy crunched the car into reverse gear and was just able to reverse the car as a corner of the back of the train bashed into the passenger door. Alan and I were stunned into silence. The train continued past us as our car that was only partly clear of the slowly moving train. It had all happened in such slow motion. Eventually, the train driver who was alerted, stopped the train.

After the grown-ups had their say with the train driver, we went on our way and continued to have our picnic under the tall tree by the Shashi river. Daddy lay on the kaross and shook his head at the bashed-in passenger door on his new car. They repeated over and over the sequel of events.

Alan and I went and played nearby. It was the rainy season and we were parked next to the dry riverbed. All of a sudden, we heard a rumbling sound which got louder and louder. The river was in spate. A huge wall of water bringing sticks and stones and any debris that was in its path came crashing past us with a resounding roar. It was mesmerising. Rapidly, the river was swollen with brown muddy water, swirling and eddying.

My mother was in no mood to bring out her watercolours. On the journey home, they were still talking about the car crash. They kept saying

“There should have been a guard on board that train!”

Then Daddy laughed. “To think, Olga you thought you could have stopped the train with your hand!” Nervous laughter.

For days and weeks, they would be heard repeatedly describing the way the corner of the train had penetrated the car door as though it was a piece of cheese. I thought the car was made of metal.

I started school in Francistown. All the children were white. Alan said that the blacks were lucky, they didn’t have to go to school, as they could not read. Mrs Harman, with dark hair and freckles, was my teacher. My mother didn’t like her very much. She was Afrikaans, and she did not have good elocution, my mother said. She pronounced the O phonetically as in ‘all’. My mother retorted it should sound like the o in ‘on’. Mrs Harman taught us how to thread a needle and we were NOT allowed to lick the thread. I did, but no one saw, so I won praise for being so quick. My mother said that Mrs Harman was wasting my time having to repeat “Cane killed Able” quite so many times. But he did kill Able! Because he was able.

In hindsight, my mother said I was really too young to be in school, aged 4. I was in disgrace when I went down the aisle in the classroom and did a little scribble in each person’s book. I wonder why I did that? I even remember doing it and even remember realising that it was a naughty thing to do. But somehow, I just couldn’t help myself! What a hiding I was given for that! So I was taken away from the school for the rest of the year. I was a disgrace to the family. I was clearly seeking attention. I was returned to the school just for the 2 months before we went to England.

“I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles” was the major song in the annual school concert.

I was given a solo part. Both teachers and fellow pupils despaired of me for incorrigibly fluffing the timing of my entry onto the stage, or forgetting my lines. That had a lifetime effect on me and ever since then, I have felt quite phobic with stage fright and a strong conviction that I had a poor sense of timing and panic at remembering lines.

Barney Balshar owned the local butcher shop. My mother and his wife, Judy, were special friends. “Auntie Judy” was so kind to me. She invited me to stay overnight which was a big thrill for me. I had never slept in such a comfortable, springy bed with sweet smelling crisp sheets. She read a story to me and tucked me in. I felt so loved.

The next day, I excitedly watched her preparing my lunch box for school, which was close to her house. She cut large slices of soft homemade white(!) bread, that had lovely blackened crusts. She lathered one pair of slices copiously with butter and sandwich spread, the other with apricot jam. The sandwiches were wrapped in waxed paper, something I had never seen before. (We never had waxed paper in our house.

But then, Judy Balshar, my mother said, was rich. My mother wrapped my brown-bread marmalade sandwiches in newspaper, brown paper… anything that came to hand.) Aunty Judy reached for a new, unused, especially bought brown paper bag. She added a peppermint crisp and some more sweeties that I had never had before. It was quite wonderful. Only I found to my horror that I didn’t like sandwich spread! Poor Auntie Judy was killed in her car a few years later at a railroad crossing.

My seventh birthday was a big event. All the children we knew were invited to the fancy-dress party. My mother baked a fruit cake in the bread loaf tin and decorated it to look like a thatched cottage with hollyhocks and ‘roses’ up the side. Chocolate icing forked on to the top formed the roof. I was in such awe that I remember being unable to eat it, as it looked so lovely.

Fay Brooks, who lived in the WNLA compound, was invited. But she chose not to come because I had hurt her feelings by inviting someone ahead of her. I was most sore at this, and my mother said that would teach me.

It was a lovely party. A long trestle table was set up under the carport. We all ran wild. I was dressed as a sunflower and my mother put lipstick on me. That was so exciting, to have lipstick! I followed her around the house as she prepared the party, asking her “Have I still got the lipstick on?” I didn’t understand why she got so angry with me asking her so frequently.

I was not a good eater. I had to be cajoled, punished and shouted at and not allowed pudding until I had eaten all on my plate. I distinctly remember always being the slow-coach at the table. How I hated vegetables! “Nonsense! You love them!” I can still see Daddy exclaim. “Cauliflower! King of the vegetables!” Porridge oats I hated, as I had to cope with all those little bits in it. I much preferred the smooth but grainy Ma’bela or Mielie-meel. But in time, I learned that all had to be eaten for the goodness’ sake and good manners.

I came home from school one day to find mother, with Alan alongside, stop me at the front door of the stoep. Their were flushed faces and both of their eyes had a sparkle .

“We have a visitor for you to meet! Now you must be on your best behaviour. Come in and say ‘how do you do’. This is Mr Hutchinson. You must say it very loudly as he is a bit deaf.”

She seemed to think his deafness was funny. I gathered myself and cleared my throat.

“How do you do, Mr Hutchinson.”

No reply.

Louder: “Good morning Mr Hutchinson.”

Alan and Mummy were just not behaving right. They were giggling too much. My shy eyes lifted to the stuffed eiderdown face of Mr Hutchinson and his motionless body. Mummy and Alan were by now in tears and hugging themselves in an effort to hide their laughter. Mr Hutchinson was the stuffed “corpse” used in the play-reading of Arsenic and Old Lace for which Daddy was rehearsing.

My bedroom gave me solace. I knew they would not follow me. Why do they keep on playing tricks on me? Why can’t I be allowed to play tricks on them, I asked myself.

My mother often sent me to visit an old lady in the hospital. Maybe she was not so old. She had had polio. I don’t remember her name. Sitting at her bedside, alone, we both struggled for conversation.

Alan and I went with the Webb children to play in the soft sand of the Tati River. Mr Webb was the new policeman in Francistown. Our parents never worried where we were in those days. We went with Robert, his brother and his sister, Jane who was nearly nine. The dry river bed was a good hundred yards wide. The golden, porous grains of sand were like Demerara Sugar.

“Let’s dig for water!” Someone suggested.

We had been sitting against a huge rock that gave all four of us shade from the burning heat. The sand felt damp in the shade, so we knew water was not far below. We scooped the sand aside with our hands, near the base of the rock.

Water! A small pool of clear water oozed into our scooped out hole.

“Maybe we will find a fish!” Alan suggested.

“Barble-fish always hide in the bottom of river water.” So we dug deeper.

It was tiring work. We stepped back for a breather. Jane lingered for just a moment. Just then, the rock, the size of a small motor car, silently flopped down into our hole. How it missed Jane, is still hard to believe. We were all very shaken and took ourselves directly back to our respective homes in very pensive moods. We realised only after the event that it was a silly thing to do and we knew we would get into big trouble. We never told our parents.

“Webby” was funny when we had the fancy dress children’s Christmas party. When I went to get my present, I said to Father Christmas, “I know who you are, you’re not Father Christmas, you’re Mr Webb!”

“Why do you always have to spoil the atmosphere?” Mummy frowned.

“But it is!”

My straight hair was curled for the event. I was dressed as a sunflower, and Alan was a sailor. My longed-for doll’s tea set was so precious.

Story and words by Fay Pearson

About Fay Pearson (neé Midgley)

I was born in Johannesburg in March 1943 when my father, Ernest Midgley (1906-1992) was Administration Officer (and District Commissioner) in Bechuanaland Protectorate from 1927-1962. My father and mother (Olga), were stationed in Tsane, Kanye, Tsabong, Lobatsi (1943), Francistown (1947-1950), Ghanzi (1950-1957), Mahalapye (1957- 1958), Machaneng, Tuli Block. When my father retired he lived in Gaborone for two years before moving to Nottingham Road, Natal, South Africa.

My father’s best station was in Ghanzi from 1950-1957 during which time I was aged 7-14. My older brother (Alan) and I went to boarding school in the Cape and Eastern Cape. During our time in Ghanzi, our unaccompanied journeys to school twice a year took us six days each.

I trained as a general nurse at Groote Schuur, Cape Town and I went to the UK to train as a midwife. I met my husband (George) in the UK when he was an Officer in the Royal Navy. We were married in Cape Town in 1967.

George and I now live in Portsmouth (UK) where I actively recount my many vivid memories of the by-gone days of Bechuanaland. I am passionate about my amazing childhood in Bechuanaland Protectorate and really hungry to share my stories.