Fay Pearson recalls life in Botswana during colonial times…

Stanley was my brother Alan’s best friend at school. He was very tall for 15 years old. He was 6’4″, thin, round-shouldered and was spattered with acne. His eyes were two horizontal slits either side of his large, hooked nose and his long neck exaggerated his bobbing Adam’s apple. His school valued his running prowess and he swept the board at athletics, winning the longer runs, such as the mile and cross-country.

Alan decreed that Stanley had to be my boyfriend. He was a brother who had full command over me. Aged 14, I wasn’t yet into feeling the need for a boyfriend, but as other girls in my class had boyfriends, I thought that I might as well have one too. Besides, he was the only partner I could get for the school’s annual ball.

Alan decreed that Stanley had to be my boyfriend. He was a brother who had full command over me. Aged 14, I wasn’t yet into feeling the need for a boyfriend, but as other girls in my class had boyfriends, I thought that I might as well have one too. Besides, he was the only partner I could get for the school’s annual ball.

Alan decided to bring Stanley to our home in Ghanzi, Bechuanaland Protectorate for the three-week June school holidays. The journey went a lot faster now there were three of us for the arduous four days by train followed by two days by road. It was all a great experience for Stanley, as his family lived in a busy gold-mining suburb of Johannesburg that had tarred roads, shops and houses close to each other.

On the long, hot train journey, Stanley taught me to play Patience. He sat well within my body-space and instructed me how to lay out the cards. We had a few no-luck games and then he had a brainwave.

“How about, for every mistake you make, I give you a kiss?”

I have never tried harder not to make mistakes! What relief it was when I won the next game without a kiss. It was a long time before I played Patience with anyone after that.

Once we arrived in Ghanzi, Alan did all he could to show off our different and isolated way of life in the wilds of the Kalahari. Most days were spent swimming in the little reservoir. Then the boys went off by themselves, taking Alan’s airgun to shoot what birds they could.

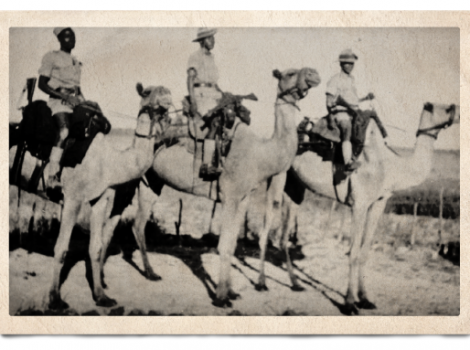

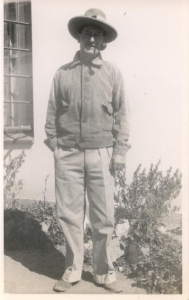

One evening Uppie (pictured left) came round. Uppie was a frequent visitor to our home. He came to Ghanzi the year before to manage a farm for Cecil John Rhodes (a descendent of the famous pioneer). Richard Upton had previously been an agricultural officer on the remote island of Tristan da Cuhna.

One evening Uppie (pictured left) came round. Uppie was a frequent visitor to our home. He came to Ghanzi the year before to manage a farm for Cecil John Rhodes (a descendent of the famous pioneer). Richard Upton had previously been an agricultural officer on the remote island of Tristan da Cuhna.

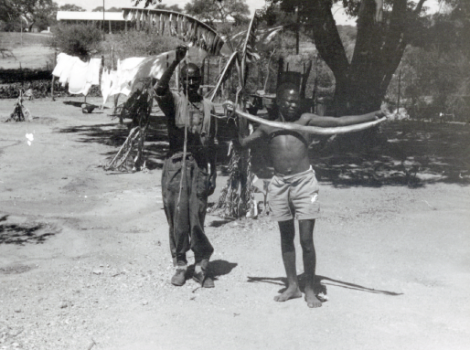

Uppie was an interesting character. He was in his late forties, I suppose. He drank heavily, but I seem to remember when he was with my parents, he was always sober. We only served him with tea. He swore that he would never sleep in a building and lived in a tent. He had the services of his trusted Boykie, who I think, was part-Bushman.

He and Uppie were a particularly good team for hunting big game, though many folk took Uppie’s hunting stories with a pinch of salt. He came to Ghanzi at a time when my parents’ social intercourse was limited to meeting the few farmers who called in at the government offices from time to time. A District Commissioner’s life was a busy one.

My parents loved Uppie’s stories and his humour. Before long my mother was getting him to provide her with stories that she would write up and sell to magazines.

“It’s a different life out here in the bush, but even here there is history in the making!” I didn’t understand that at all. History? History was boring dates and facts.

Uppie also had experience in taxidermy which he spent many hours teaching Alan. This sent the boys out into the bush with the airgun. They shot mostly ring doves and grey loerie which we called go-way birds. These were the bane of hunters, as they made a shrieking cry that sounded like “Go away”, and that alerted animals that danger was approaching. This was Uppie’s world, and he was at home in it. On the evening I want to tell you about, Uppie had my parents’ full attention with a drama that he had uncovered out in the bush. He believed that a bushman had been savaged by a lion. Uppie had just returned from driving him three hundred miles to a hospital, in vain.

I have the full testament account…

I came across Alan and Stanley in a huddle and whispering in a dark corner of the stoep.

“What’s going on?” I asked, lowering my voice to their level.

“Go away. This is men’s talk”. Alan hissed.

“Talk about what?”

“Not telling you”

“Why not?”

“Because it is dangerous”.

“What is dangerous?”

They looked into each others’ eyes for one to make a decision.

“OK, you can join us, but can you be trusted?” Alan sighed, looking up.

“Cross my heart!”

“Well…” Stanley certainly had an alarmed look on his face.

“Come on!” My impatience became desperate.

Alan blurted out what sounded like one syllable.

“We-are-going-to-kill-a-Bushman.” Then he let his breath out in a hiss.

“Why?” I needed to know.

“Oh don’t be so stupid! Why do you think?”

“Because they are there?” I didn’t expect praise for my logic.

“Ja, you’ve got it in one. But this is dead serious! So you are not to blab to anyone about this, ever! Do you hear?”

Stanley’s eyes were narrower than ever and he remained silent. I could see him holding his breath.

“When?”

“After supper”

Enthralled with Uppie’s story, our parents didn’t seem to notice that we children were unusually quiet over supper. I was too fearful to speak in case I let something slip.

“Can we be excused from the table, please?”

Our parents were relieved to let us go, so they could get on with grown-up talk.

“We are just going outside to look for shooting stars”.

In those clear winter nights we could see the silent star shoot across the sky with a dash of streaming sparkly yellow light trail every few minutes. Somehow it seemed incongruous that it was silent. Once we were out of ear-shot of the house I wanted to know our plans.

“Where are we going to look for a bushman, Alan? Anyhow, you can’t shoot a bushman with an airgun!”

“Don’t worry; I know just where to go. If you hit him in the right spot, he will drop like a stone.”

He had been impressed with the story of David and Goliath. Now it was his turn to be David and astonish Stanley. We followed him, backs bent and creeping only in the shadows as far as Daddy’s office. The full moon cast Bushman-shaped shadows from the bushes onto the sandy patches of limestone soil, still warm from the long hot day. Sheppy, followed us excitedly, wagging his tail. He then nudged up to me as we sat on the stoep in the front of the office.

“You stay here” our leader commanded. “I’ll take Sheppy and I’ll scout for a Bushman and come and get you when I have found one.”

Stanley and I obeyed and waited, listening to the soft pat of Alan’s footsteps fading into the shadows. “Com’ on, Sheppy!” Alan patted his thigh. We could hear the metallic tinkle of a goat’s bell, the occasional bark of a dog. The cicadas started up their loud hiss. Stanley looked scared.

“He will be ages yet” I said.

“Has he done this before?”

“No. At least, I don’t think so, but then, he may not have told me”.

I didn’t know why Stanley moved closer to me.

“Do you like me?” Stanley asked.

“Yes”

“How much?”

I didn’t know how to answer that question. How could I know how much? I just shrugged. I was puzzled by Stanley’s line of questioning, but wanted to I avoid hurting his feelings. I welcomed the opportunity to change the subject.

“Oh look!” A shooting star trailed across the sky.

“Where?”

“You just missed it. It was over there”

We watched the speckled navy sky lit by a three-quarters moon. My eyes rested on my favourite, the Southern Cross, the only constellation of which I was always certain to recognise.

“Are you enjoying this holiday?”

“Yes”, he said “It is one of the greatest adventures I have ever had in my life. My parents didn’t want me at home these holidays because of mother going to hospital, so it worked out well. It’s nice to be with people who are so kind to me”.

I was not aware of kindness from any of us. I just thought Alan wanted someone to show off his bushcraft to his friend. Stanley went on to talk about school; how he had found school life difficult. I did not have the heart to tell him that because of him, my life too, was difficult back at school.

“Camel! That’s the name of your boyfriend! Camel!” Val had said in the classroom, right there, in front of all the others.

“This is how he runs!”

They were all watching, gloating, and craning their necks to see her performance. She believed that she had mimicked a camel but I thought it looked more like a stalking heron. She may have looked a fool, but I felt a worse one for having such poor taste in being friendly with a camel.

“He is awful!”

“How do you know? You’ve never met him”. I retorted sulkily.

“There is no need! One look at him and you can see what he is like!”

I searched for an ally in the room. They either turned to their books or to each other with eye-holding smiles. I now understood why poor Stanley found our friendship valuable; I only wished it were not with me. Stanley marvelled at the bush country at night.

“It is amazing out here; not a light, and no tarred roads or pavements. Are there any tarred roads in Bechuanaland at all?”

“The only one that I know of is the short strip in the main street of Francistown. But I do know there is not a single traffic light in the entire country!”

Stanley shook his head in amazement. I shovelled my bare feet into the warm white lime soil. The cement stoep was beginning to lose its warmth.

“And you have the capital of your country in South Africa! In a different country!” He guffawed.

“Oh golly! There’s a snake!” I interrupted with a whisper.

A long, long dark snake wove from behind the office towards the bushes a mere five feet away. Because of its speed I knew it must be a black mamba, the most deadly of all. I felt Stanley’s frame go rigid. The cicadas went silent and seemed to be watching us.

“Keep very still. It hasn’t noticed us. If we don’t make it feel threatened it will go on its way. I was proud of my brave words, as I really was very afraid. We waited and watched.

“We can’t go yet. There may be a mate following it. Wait.!”

The wait seemed interminable. Our wide eyes swivelled in our still heads. Eventually, we had to move.

“Let’s go back to the house” I said. We had got bored waiting for Alan.

As we came through the gate into our back yard I saw the carbide lamp swinging in Daddy’s hand, as he stood in the doorway of the kitchen gauze-netted door.

“Fay! Is that you? Where have you been? What on earth have you been up to?”

Stanley followed sheepishly behind. Mummy came up behind Daddy; then Uppie. Over his shoulder I saw Alan inside the house nonchalantly stroking Molly the meerkat. He strolled into the sitting room, where the Tilly-lamp hissed out its bright light. His lips were smiling, but not his eyes.

“What were you doing out there, at this time of night?”

I gulped and couldn’t answer. Could I really say to them that we had been out there to kill a bushman? They would never have believed me. They were so angry. Accusations poured over me like lava that turned me to stone. Daddy hit me, and I was directed to bed.

“What a fool you have made of myself” Mummy shouted,

“Chasing Stanley like that! He doesn’t need you chasing him around like that. Why can’t you leave him alone? What did you think you were doing going out in the dark with him? He has come here for a holiday with Alan; not to be chased by you! Alan tells us that…”

They were impervious to my protestations. Daddy hit me again and sent me to bed. I went disconsolately to my bed on the stoep. Later Uppie came to my bed and sat down quietly. He took my hand and spoke to me so gently and kindly that I started to weep.

“I think your Mum & Dad were just worried about you.”

“They weren’t worried about me at all! They were angry with me because they believe I was chasing Stan, but I swear I wasn’t!”

“There, there,” Uppie soothed. “I believe you. It’ll be OK in the morning. You just go to sleep and I will talk with them”.

He pulled the karross up to my face and I felt the fur tickle my cheeks. As always, sleep gave me the desired release.

Story and words by Fay Pearson

About Fay Pearson (neé Midgley)

I was born in Johannesburg in March 1943 when my father, Ernest Midgley (1906-1992) was Administration Officer (and District Commissioner) in Bechuanaland Protectorate from 1927-1962. My father and mother (Olga), were stationed in Tsane, Kanye, Tsabong, Lobatsi (1943), Francistown (1947-1950), Ghanzi (1950-1957), Mahalapye (1957- 1958), Machaneng, Tuli Block. When my father retired he lived in Gaborone for two years before moving to Nottingham Road, Natal, South Africa.

My father’s best station was in Ghanzi from 1950-1957 during which time I was aged 7-14. My older brother (Alan) and I went to boarding school in the Cape and Eastern Cape. During our time in Ghanzi, our unaccompanied journeys to school twice a year took us six days each.

I trained as a general nurse at Groote Schuur, Cape Town and I went to the UK to train as a midwife. I met my husband (George) in the UK when he was an Officer in the Royal Navy. We were married in Cape Town in 1967.

George and I now live in Portsmouth (UK) where I actively recount my many vivid memories of the by-gone days of Bechuanaland. I am passionate about my amazing childhood in Bechuanaland Protectorate and really hungry to share my stories.