The early years

Quett Ketumile Joni Masire was born in Kanye, Botswana on July 23, 1925, to Joni Masire, a farmer and Gabaione Kgopo. Typical of the era, Masire’s childhood years were spent as a herd boy but he excelled in academics and graduated at the top of his class from Kanye School. His love of education and outstanding academic achievement gained him a scholarship to further his education at the Tiger Kloof Institute in South Africa, from which he graduated in 1950.

Son of a minor headman, Sir Masire grew up in a community where male commoners such as himself were expected to become low-paid migrant labourers in the mines of neighbouring South Africa. From an early age, Masire set himself apart through academic achievement. During school breaks, he supported himself by selling refreshments at local football matches. Despite continued good grades, his ambition to attend university was frustrated by financial and health constraints.

Following the death of both his parents, he earned a teaching certificate and worked at the Kanye Junior Secondary School to support his younger siblings. He worked hard to save money, ultimately buying a tractor and subsequently taught himself dry farming.

In 1950, after graduating from Tiger Kloof, Masire helped found the Kanye Junior Secondary School (now Seepapitso II Secondary School), the first institution of higher learning in the Bangwaketse Reserve. He served as the school’s headmaster for five years. While teaching, Masire got into farming and in 1957 earned a Master Farmers Certificate and established himself as one of the territory’s leading agriculturalists.

Masire’s modern farming methods of cultivation were initially derided by some but big yields silenced the naysayers. In 1957 he became the first indigenous African in the Bechuanaland Protectorate to be awarded a Master Farmer’s Certificate. Perhaps the greatest tribute to Masire’s leadership was the award he received in 1989 from the Hunger Project in recognition of the improvement in nutritional levels throughout the country between 1981 and 1988, despite the onset of severe drought.

Birth of a leader

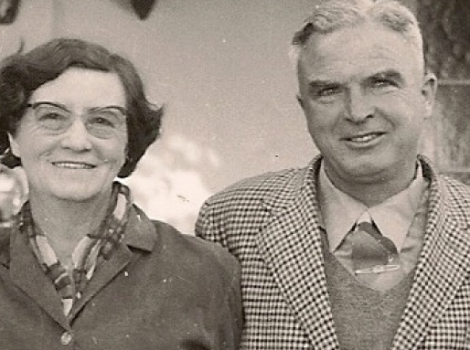

In 1958, he married Gladys Olebile Molefi, who died in 2013. They had six children, who survive him, as do 10 grandchildren and four siblings. That same year he was appointed the protectorate reporter for the African Echo/Naledi ya Botswana newspaper. He was also elected to the newly reformed Bangwaketse Tribal Council and after 1960, the protectorate-wide African and the higher Legislative Council, being the only commoner from the southern Protectorate to be elected to the latter body.

Although he attended the first Kanye meeting of the People’s Party, the earliest nationalist grouping to enjoy a mass following in the territory, he declined to join the movement. Instead, in 1961 and 1962, he helped organise the rival Democratic Party, serving as its Secretary General.

Seretse Khama and others approached Masire to play the leading role in organising what would become the BDP. Masire was working as a journalist for the Naledi ya Batswana and African Echo newspapers when he first met Khama at a community meeting. The two had a symbiotic relationship; Khama had the vision for a democratic post-colonial Botswana, while Masire had the enthusiasm and community ties to rally support. From the beginning, the Democratic Party was dominated by Seretse Khama, its popular leader and Masire, its chief organiser.

One of the principal reasons for the party’s early electoral success was Masire’s energy; in one two-week period in 1964, for example, while campaigning in the remote areas of the Kalahari desert, he travelled across some 3,000 miles of sandy tracks to address 24 meetings. Besides spreading his party’s message, he used such junkets to build up a strong network of local party organisers, many of whom were teachers and/or master farmers.

He also was the editor of the party’s newspaper, Therisanyo, which was the protectorate’s first independent newspaper. Drawing on his many newspaper and educational contacts, Masire quickly established an organisational network that became the basis for the party’s landslide 81% of the vote in the 1965 general election.

In 1965 the Democratic Party won 28 of the 31 contested seats in the new Legislative Assembly, giving it a clear mandate to lead Botswana to independence. The following year Masire became the new nation’s Vice President, serving under Seretse. Until 1980 he also occupied the significant portfolios of finance (from 1966) and development planning (from 1967), which were formally merged in 1971.

Masire post-independence

As the nation’s first Minister of Finance as well as Vice-President, Masire championed a series of robust interventions to elevate Botswana out of its then prevailing status as one of the world’s least developed countries, which in 1966 had an annual per-capita income of only about US$ 60. His program included channelling foreign aid, loans, and mining revenues into the development of educational, health, power and transport and communications infrastructure, while encouraging small-scale services and industries. Efforts were also made towards promoting commercial agriculture.

At the time of independence, the United Nations listed Botswana among the world’s least developed nations, with little running water or electricity and few paved roads. The geographical challenges were great for landlocked Botswana; largely made up of desert sand, farming was virtually impossible.

“When we asked for independence, people thought we were either very brave or very foolish,” Masire was often quoted as saying.

About a year after Botswana became independent, the De Beers company made a mining discovery on the eastern edge of the Kalahari Desert that gave the country the glittering hope it needed: diamonds. But Masire and Khama saw to it that De Beers did not simply plunder Botswana’s resources, as many big companies had historically done in Africa. Instead, De Beers entered into a 50-50 joint venture with the government. Today, diamonds are as synonymous with Botswana as cigars are with Cuba, accounting for more than 60 percent of the country’s exports.

In the early years of independence, Masire’s dynamic approach was unpopular with some conservative bureaucrats, while others resented his pre-eminent influence over national policy planning. But, Seretse maintained his faith in his deputy.

By the end of the 1970s, the success of Masire’s development portfolio had gained him increasing international as well as domestic respect and political clout.

The rise of a robust leader

From 1966 to 1998 Botswana enjoyed the highest annual economic growth rate in the world. The resulting rising revenues allowed for further investment in infrastructure and public services, as well as human resource development, with education and health consistently taking the lion’s share of the budget.

Masire and Khama leveraged the newfound wealth to add schools, improve health care, build infrastructure and modernise farming. The development helped Botswana maintain stability through droughts and a slump in diamond prices in the 1980s. Tourism began to flourish, especially wildlife tourism.

Laura Alfaro, a professor at Harvard Business School who interviewed Masire in 2002 for a case study she co-wrote called “Botswana: A Diamond in the Rough,” said that unlike leaders who “want to build palaces and statues,”

Masire said, “No, I’d rather build schools.”

Stepping up following Seretse’s death

Five days after Seretse Khama’s death on July 18, 1980, Masire was elected president by secret ballot at the National Assembly. With the overwhelming support of his party’s Parliamentary caucus, Masire presided over the late Sir Seretse’s unfinished term until 1984, when he led his party to victory in his own right. He subsequently returned to the presidency through the Democratic Party landslide victories in the 1984 and 1989 general elections.

On his first Independence Day message as President, Sir Ketumile Masire made a timeless promise to a nation reeling from the loss of a leader; a promise he went on to live out and saw fulfilled:

“Sir Seretse Khama has bequeathed us the unity of our nation, the democracy of our political and economic institutions, as well as the socio-economic progress we have achieved since our independence.

If for any reason, we would wander off course, the fault shall not lie with our departed leader, but with us, the living. Let us, therefore, pay tribute to the founder of our nation by rededicating ourselves to the ideals and principles for which he stood and worked so hard for.

Let me assure you as your President, that for my part, and that of my government, we shall serve the nation to the best of our ability. We shall endeavour to pursue and perfect the policies on the basis of which we were returned to power so convincingly in October 1979.” Sir Ketumile Masire, 1980.

Seeing the country through a severe drought and an early 1980s slump in diamond sales, Masire’s tenure was characterised by continued high rates of economic growth and social development. This was marked by Botswana’s achievement of the highest annual economic growth rate in the world, which saw the country reaching middle-income status among nations globally. As surrounding countries struggled with violence and corruption, Botswana became a model often referred to as “the African exception.”

Most of Botswana’s growth came from diamonds, the nation’s leading export earner. Expanded revenues allowed Masire’s administration to expand social services considerably, particularly in education, health, and communications.

Under Masire’s leadership, Botswana continued to enjoy its remarkable post-independence economic growth rate of some 10 percent per annum, one of the highest in the world.

Despite Botswana’s enviable record of development in the 1980s, many problems remained, none more difficult than the rapid spread of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS in the 1980s. Although the government provided free treatment and still does, Botswana continues to have one of the highest rates of HIV in the world, ranking among the worst hit in the world.

Masire was the 1989 Laureate of the Africa Prize for Leadership for the Sustainable End of Hunger, and was cited for his sustaining efforts to develop nutrition, health, education and housing.

In 1996, the United States agreed to give Botswana $203 million in aid over three decades. In September 1995 AID (Agency for International Development) had shuttered its bilateral mission in Botswana, asserting the nation had “graduated” from foreign assistance. According to Masire, it was a rite of passage the nation had been preparing for all along.

“We used to say to our donors, ‘Help us to help ourselves, and the more you help us, the sooner you will get rid of us,”‘ he recalled.

Masire, the latter years

Sir Ketumile’s legacy goes beyond our borders, as he also played a key role as one of the leaders of the Frontline states in the liberation of our region from colonialism and Apartheid. After leaving office, Sir Ketumile divided his time between his passion for farming and frequent service as both a domestic and global statesman, often working through his Sir Ketumile Masire Foundation. Masire set up the Sir Ketumile Masire Foundation in 2007 to promote the social and economic well being of Botswana. He also co-founded the Global Leadership Foundation to promote good governance and resolve conflict through mediation.

Long after he stepped down as Botswana’s president in 1998 — there were no term limits at the time, but Masire helped establish them. Masire was often asked how the rest of Africa could be more like Botswana. He would answer, softly, with thoughtful pauses, that the keys to success were government transparency, a resistance to corruption and a willingness to follow the rule of law.

“Corruption is an evil. It is something that has really ruined the economy, the morals and everything of value in a society.”

Sir Ketumile, the diplomat

Sir Masire retired as president in 1998 but continued with diplomatic initiatives in Africa.

He chaired the Panel of Eminent Persons, the panel that investigated the 1994 Rwanda genocide, coordinated the Inter-Congolese National Dialogue among other peace initiatives in South Africa, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Mozambique, Ghana and Swaziland. Up until the time of his death, he remained a respected voice for peace and good governance on the African continent and beyond.

He was chairman of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and vice chairman of the Organisation of African Unity. He was also chairman of the Global Coalition for Africa and a member of the UN group on Africa Development.

During this period, he earned three Honorary Doctorates of Law (L.L.D.) from two universities in the United States and one in the United Kingdom. He also earned two Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from two other universities in the United States.

In 1989, he was awarded the Africa Prize for Leadership for the Sustainable End of Hunger and the Grand Counsellor of the Royal Order of Sobhuza II in Swaziland.

Masire also earned Namibia’s Order of the Welwitschia, which is one of the highest honours of the land.

Sir Ketumile truly touched many lives both in Botswana and elsewhere. However, above all, we will always remember Rre Rra Gaone for his character, his humility, wit and decency, which personified the values of Botho that our culture is heavily steeped in.

References: www.nytimes.com, Africanews.com, Washingtonpost.com, http://biography.yourdictionary.com