On the way home for one holiday, we were close to the border on the South African side when we came across a truck that had collided with a cow. The truck was badly damaged and had just caught fire. My father immediately jumped out of our Land-Rover and into the truck to retrieve the driver who was unconscious (my father was a big, strong man well able to do something like this unaided).

My father gave him some basic first-aid and we waited with him for the next vehicle to help. The vehicle immediately went to the next town to get medical assistance and also phone the border post (there were no mobile phones in those days) to stay open late for us. The border staff were still waiting for us when we arrived.

At the end of my first year, and my sister’s second, we were moved to boarding schools in Johannesburg. There were different challenges here. We went to different schools and probably the biggest difference was the academic year; my sister’s school operated a 3-term system, and my school a 4-term system. As a consequence, we really only saw each other at Christmas and Easter.

I was extremely fortunate with this move, as my school was close to the home of a friend in Bechuanaland, and his mother, an absolute angel, would pick me up every Friday afternoon from school, and either she or her neighbour would take me back every Monday morning. She rapidly became known as my ‘second’ mother, but in many ways, she was more influential over me than my mother; she brought joy and happiness into my life after the despair of my first year of boarding school. Subconsciously I think I blamed my parents for my unhappiness at the first boarding school.

This was also my first exposure to the ugly face of racism in South Africa, when the school boys nicknamed me “The Botswana Kaffir”. I took this as a direct insult and very soon it was only used by groups of boys, or those much bigger than me. I simply did not understand why the people I lived with were now considered inferior people; they had done me no harm.

Travel to the Johannesburg boarding school was by steam train. Most people hearing this are immediately jealous because of the perceived romance of steam train travel; there was no romance in it. We travelled in a compartment for 6 people, and it was generally full.

These compartments were neither air-conditioned or ventilated. There was an openable window and one either opened the window only to get a blast of soot-laden smoke in your face and the compartment or keep the window closed and sit in a sauna; there were no other options.

The train timetable didn’t always coordinate well with school holidays and on a few occasions, I had the joy of spending an extra day in boarding school on my own at the beginning or end of the holiday; there is no place more lonely than an empty boarding school. The South African school holidays also didn’t co-ordinate with the Bechuanaland schools, and some holidays were spent alone at home during the day, as Dad was working. Mum often used to teach at the local schools and my younger sisters were at school. The highlight of these days was going down to the police station and having a meat pie with Dad for lunch.

These train journeys were not without incident either. On one journey, one of my room-mates had light fingers and took advantage of having to disembark late at night to rifle through everyone’s possessions and make off with our money. He was caught shortly after he left the train. On another journey, it turned out that one of the gentlemen in my compartment had been arrested by my father while in Maun for urinating in public.

This came out as the train crossed into Bechuanaland and he flew into a rage about what my father did to him (locked up in a multi-racial police cell overnight) and what he would do to my father if he met him again. I was absolutely terrified in case he found out who I was. When I spoke to my father about this, his simple explanation was;

“When visiting your friend, if you need to relieve yourself, you use the bathroom, you don’t urinate on their lounge floor.”

Leaving paradise

So, why did we leave paradise? Did we have to leave? I will start with my father’s explanation. He told me that after independence, Sir Seretse Khama approached him and other senior expatriate police men and explained to them that because Botswana was a newly independent African country without an army, he didn’t feel able to allow them to continue in their roles as the police effectively ruled the country.

In addition, they were from the UK, which may have devalued their independence. He gave them 3 years to find an alternative career, failing which he would discharge them. I am unclear whether they were also asked to leave the country.

At the time of independence, all the expatriate families were offered citizenship, which my parents did not take up, much to my regret.

My father started looking for an alternative career; his explanation for this was that he was uncomfortable staying in Botswana having been in a senior police role, fearing retribution. That was his view and in fairness, there was a lot of concern about the future post-independence amongst the expatriate community. And in his case, the British had not treated Sir Seretse and Lady Ruth with the fairness one would have hoped for.

He considered returning to the police in the UK but was told because he had been out of the UK for about 11 years, he would have to start his police training from the beginning and re-take all of his exams, which he wasn’t prepared to do. He also considered taking the family to Australia to go sheep farming in the Outback but decided against that. He decided that the future lay in South Africa, and he admired the Nationalist Government as it was a strong government.

I have never understood this choice and his admiration for them does not sit easy with me. When the South Africans heard he was looking to move, they tried to recruit him into the South African Police, but he declined because philosophically, he did not agree that police should be armed in the normal course of their duties. He was trained to be a marksman with the UK Police.

This was also the time when diamonds were found in Orapa, and De Beers offered him the role of Security Manager for the mine, which he turned down, ostensibly because he thought it would not be possible to perform his duties because of his police background.

Considering that this was a joint venture with the Botswana government and my parents knew Sir Seretse and Lady Ruth privately, it is difficult to understand his logic. Anyhow, we moved to Cape Town in South Africa in December 1968. Me, my brother and sisters were sad to leave, we didn’t want to, but had no choice.

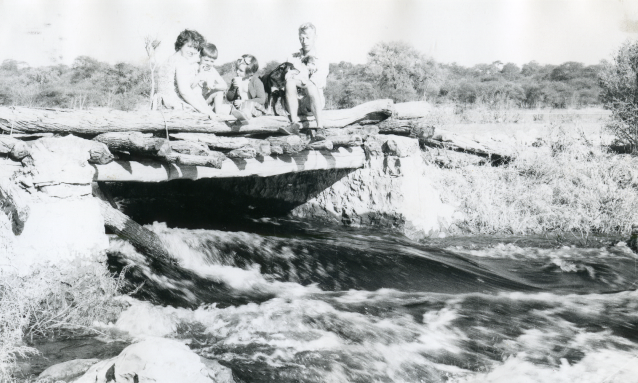

I have been back to Maun on a few occasions, and it never disappoints its children; it looks after you. I visited in about 2000 with my mum and my two daughters. I often told them stories about life in Maun, particularly the wildlife. We went to see our old house, and while looking across the river, we saw two zebra grazing on the banks.

Immediately my daughter said to me,

“So it’s true daddy about all of the wild animals.”

And in 2017 I brought my new partner to see Maun, we were staying at Backpackers near the bridge. We walked along the bridge, and there was a father teaching his son to catch fish in the same place my father had taught me. Later that morning, we caught a taxi into town and I started chatting with the driver. After a while, he said to me;

“I know you are telling the truth because you are telling me the same stories my grandfather told me.”

That was a wonderful compliment, knowing that is how the Tswana people pass their history and culture on to their descendants.

Written by Ian Brooks

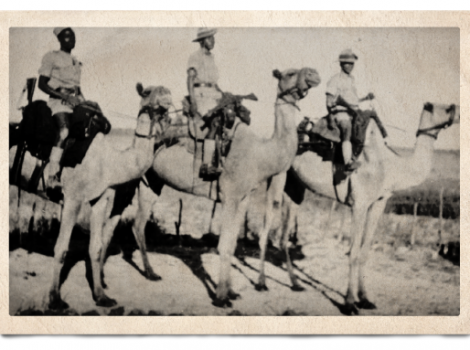

Ian is Donald Brooks’ son. His father arrived in Maun in early 1962, leaving four years later in 1966. He was a police officer, trained in the UK, but working in the Colonial Service. His brief on being transferred to Maun was to sort out the ‘w’ element; there was a perception that there was insufficient regulation, particularly the hunting of the wild animals, and his task was to bring this under control.

Ian and his siblings were children while in Bechuanaland Protectorate/ Botswana; the younger 3 children were born in Bechuanaland Protectorate. The context is a combination of his own memory of life in Maun as a child, as well as various conversations with his parents over the years about the photographs and life in Botswana while they were there (1958 to 1968).

Interesting staff,