Isaac came to work for my family in Francistown when he will have been a mere teenager, in 1949 (mainly to help my mother in the kitchen). I remember his arrival when I was six years old. He readily followed us to our several different homes, some of which were many hundred miles apart, in Bechuanaland Protectorate. Being illiterate, he will not have maintained contact with his own family in the north of the country. It will have been a prestigious job for him, to work for the “Molaudi” (District Commissioner) with many an extra comfort that he would otherwise not have achieved in any other avenue, at that time. With no industry, public transport, shops, schools, medical facilities, jobs were hard to come by for anyone in the old Bechuanaland Protectorate.

My father retired from his British Government occupation in 1963. (two years before Independence of Botswana.) My parents moved to Natal, South Africa, where the Zulu people were a completely different tribe and nationality. It was commendable that Isaac chose to follow with my family to a country where all the black people spoke Zulu, a language that would have been totally strange to him. But he insisted on staying with my family in South Africa for a further eleven years. He insisted they would not have managed without him.

Sadly, Isaac succumbed to the effects of alcohol and became no longer reliable or useful. In Bechuanaland, it had been illegal for black people to drink alcohol; not so in South Africa. Isaac eventually left my family’s employment in 1975.

So he was retired to his home country, Botswana, taking with him, his son and his little daughter; leaving the Zulu wife behind in South Africa. It was a mutual wrench to see him leave having been so part of our lives for so many years, but it was best for him to return to his home and his family. They knew it would be the end: that they would lose all contact with Isaac, due to his illiteracy.

Isaac had always been cheerful and had a ready sense of humour that was shared well with my parents. My father could blow some noisy temper tantrums that never bothered Isaac personally; it simply sent him into fits of giggles. Years after he had returned to his homeland, I longed to learn how Isaac had fared. I yearned too, for him to learn how and when my parents had ended their lives. My mother, in particular, had not found me as an easy child and I thought that if I were to meet Isaac again, he might cast some light on my mysterious childhood. I often longed to have heard his point of view.

My first visit to Botswana in forty years, in 1999, was with my husband George. The purpose was to visit as many of the homes in which I had lived; all of which were all still standing. I began to wonder if I would bump into Isaac. Peering into crowds of black faces, the needle in the haystack seemed impossible. He could be anywhere.

He could have returned to South Africa; he could have died. It became a quest. We visited Jimmy Haskins, the large consortium in Francistown. I remembered that my father said he had sent a monthly pension for Isaac to Jimmy Haskins himself, but Jimmy died a couple of years before. The name meant nothing to the personnel department. In Francistown, we saw hundreds of people but few elderly.

In the large dining room in our hotel in Francistown, I saw an elderly, well-dressed African gent standing to one side, back to the wall, observing the guests. I thought;

“He looks about the age Isaac would be! Having taught Isaac to cook, my mother had wondered whether Isaac would get into the hotel trade.”

I beckoned to him. He inclined his head, and then slowly sat down at the table he had been standing next to! What a gaff! He is a guest! So as soon as I was able, I went over to him and apologised. I told him I thought he was the Manager. His face lit up from my unintentional flattery. His English was limited. He said he came from Malawi, so would not know Isaac. I became utterly disheartened that I would never find Isaac.

One day in 2010, while idly browsing the Internet, I looked up “Botswana Newspapers”. Finding two papers with a “Contact Us” section, I emailed them to ask how I could advertise to find Isaac, stating his history very briefly. No reply.

Then a month or so later I received a surprise phone call from an Edwin Batshu, the then Deputy Commissioner of Police of Botswana. He had seen my advertisement in the paper. I had no idea my advertisement had been published. He said that Isaac was a distant relative and was herding his cattle in the remote northern village of Maitengwe on the border of Zimbabwe.

“You got the surname wrong: it is Motsusi, not Matusi, and will you please stop crying!” Edwin was clearly one to take charge.

“Do you remember that Isaac used to have a gap between his front teeth?” Edwin asked.

“Well it is wider now… much, much wider!” he laughed.

“Isaac went blind, but he had an operation, and now he can see a little.” he continued.

“Yes, the old man; he is well,” Edwin added in typical phrasing.

Eight months later, I saved enough money to pay my fare to visit Isaac. In September 2000, our 28-year old son Alistair flew from New York where he was working and joined me in Cape Town a few days before we flew to Botswana. Unfortunately, husband George was too tied up to join us.

Edwin Batshu and his advisor to the Botswana Police, Peter Viner from the UK, gave us a warm reception in Gaborone and joined us for dinner at our hotel. At the end of the meal, Edwin brought all his family to the hotel to meet me. His four children in immaculate new-looking clothes stood in a straight line to be introduced to us. Then his wife quietly came forward. She was a high-school teacher. A beautiful family now in successful jobs abroad.

The next day, we were to be taken to North Botswana to meet Isaac. 500km. Leaving before dawn the next day, we travelled north in convoy with our host Edwin Batshu. En route, we stopped at Palapye to meet Edwin’s policeman brother, Head of Traffic. He warned us not to speed! No nepotism, here, I thought. The good roads were tarred all the way, although in Botswana there is always the lethal hazard of stray donkeys, cattle and goats grazing at the roadside.

Alistair was impressed with the supermarket in Francistown that he said was better than any he knew of in Manhattan. (But then Manhattan does not have much space for supermarkets. It is all Deli shops there). We stocked up on supplies for our visit. Halfway between Francistown and Nata, we turned off north to continue the 100k on the excellent tarred road to Maitengwe. Wooden poles were laid along the side of the road, in readiness for Maitengwe soon to being supplied with electricity.

We arrived in Maitengwe in the late afternoon. A live owl had found its way into the sitting room down the chimney. It was sitting bedraggled and unhappy in the fireplace. It had probably for some time so we were relieved to be able to free it quickly. We were just in time to be given a quick drive around the immaculate village. (They compete for a prize for the cleanest and tidiest area).

We stayed in Edwin’s “holiday house”, a three-bedroomed brick bungalow immediately next to the round, thatched mud huts of his closest relatives, including his tall and upright 80-year old mother. It was to be a new experience for Alistair as well as me, to be staying in 40c heat in an African village with even the locals complaining of the heat! I enjoyed being reminded how we coped when I was a child in remote Ghanzi, in the Kalahari Desert, when we had no electricity.

Here in Maitengwe, we were only able to fill our jerry cans from the tap in the yard after a very late hour when the village was less demanding on the supply. Edwin claimed to have no domestic knowledge, so I was cook for the two-day visit. In a kitchen that was an annexe to the house, there was a cooker with a gas bottle attached. Edwin kindly filled a bathtub with water for us to enjoy two welcome baths a day, with water heated in pots on the cylinder gas stove in the detached kitchen building.

Little old Isaac, looking twenty years older than his sixty-eight years, came shuffling along over the red sand to Edwin’s house. In spite of the hot weather, he was wearing a tatty old hat, jersey and jacket. He had greatly shrunk in size, and his missing front teeth revealed an ever-mobile bright pink tongue. His footsteps were silent on the grassless red earth. He stood before me. I could not speak.

“Do you know who am me?”

He then removed his thick, badly scratched glasses that seemed to help his eyesight only a bit, hoping that would help my recognition.

“Yes, Isaac, I see it is you.”

I took his rough, dry hand. His melodious voice was gentle;

“Why are you so merciful to me? I feel so heppy, I want to climb a tree and flaa (fly)!”

This he repeated many times, shaking his head with disbelief. He carried enormous guilt at having to leave my parents, due to his drunken irresponsibility. Edwin sat him down and gave him a can of beer. Soon he was sharing reminiscences with me. Whenever I reminded him, he responded with a vigorous, “I know, I know!” His favourite conjunction was the word “udderwaas” (otherwise).

Isaac peered into Alistair’s face.

“Ah laak his smaal! He always smaaling!”

It worked, Alistair’s smile returned.

“‘Medem’ and Morena very kaand to me. They never angry with me for nothing,” he went on and shook his head slowly.

We reminisced how my mother would sing, in her lovely contralto voice, accompanying herself on the piano, almost as a routine after supper.

“I know, I know! So naace, that music! One time, I hide behind the door to listen after I say goodnight, to go to bed. Ah, ah, ah, so naace music!”

He sighed and took another slug of Castle beer.

“They think I not there!!”

His wrinkled hands were too old and cold to warm the can of beer he clutched as he grinned. His usual all-day favourite tipple is “Chibuku” (5% alcohol) an African beer that is sold in waxed cartons.

“One night, medem, she find me, sitting there listening behind the door.

She say, “What you doing there, Isaac?”

I tell her, it is my leg. My leg, my leg give pain. She give me muti and tell me to go rest my leg”

“What was the muti she gave you?

“Aspirin” She always give aspirin.

“Did you take the muti?”

“No, my leg was heppy! It did not need muti! Not at all!”

He chuckled shaking his head. Another memory returned to him.

“Sometimes Morena get very cross. Shouting! Shouting! If his papers moved by medem, he say,

‘I will kill whoever moved my papers!’ Such a big noise!” He laughed.

“I know. I never touch Morena’s papers,” he became pensive.

In due course, we learned that Isaac’s son, David, “later went off the rails” and Isaac lost touch, or is estranged from him. Isaac’s beloved daughter, whom he brought from Natal was Gloria. She died of AIDS a couple of weeks after her first child, Moluki was born, (Well, one assumes it is AIDS. They never admit it. They just say,

“She/he just got sick and died!”)

Isaac actually “works” away out in the bush, tending Edwin’s cattle, and comes to Maitengwe perhaps monthly to collect the occasional supplies and to see his grandson and collect his government pension, most of which he spends on his favourite “tipple”, Chibuki. His needs are so few that it put some perspective on my life.

The following morning, Edwin left us for a few hours to attend a local funeral. The chubby-faced 2-year-old grandchild of Isaac, Moluki was brought to see me. His young father, Lazerus, spoke good English and wrote his address down for me. He had a lovely handwriting. He was praised all around for the devotion and excellent fathering Lazarus gave him with no female support that was admitted to. The little one had been to the clinic that morning and was said to have Tuberculosis. My nurse training made me wonder whether he also had measles. He had a rash, runny nose and a fever. He enjoyed my ‘Princess Diana’ cuddles and soon came out of his shell by holding on to me and laughing and smiling with large black, watery eyes never leaving my direction.

We were visited by so many folk from the village. One man who was particularly keen to meet me was the local hereditary Chief, Willard Mengwe. He used to be the interpreter for my father’s court-cases in the Ghanzi district as he was for many other government officials. Chief Willard very kindly gave me a gift of a sepia pastel of Seretse Khama, Botswana’s first Prime Minister. One of Chief Mengwe’s daughters was living in Larvik in Norway.

The chief’s memory of my father as District Commissioner was his rigid ruling with court cases.

“He was never too lenient, nor too strict. Right by the book… not like me!” Willard smiled.

Edwin was amazed when Chief Willard said that my father rarely drank alcohol. Edwin’s image of DC’s of those days was that they probably “all” drank heavily and did as little as they could so that they were less or noticed in Mafeking for their inadequacies!

We were taken from one cluster of huts to another and introduced to the whole village as well as several schools. Soon we learned the different local Kalanga language of greeting, saying,

“Mamuka: How are you?” and “Tamuka,” meaning: “I am well.” Very different from the usual “Dumela”, the usual Tswana greeting I remembered from the olden days.

We disrupted several schools by our presence. Fresh-faced, happy, tittering children gently pushed against each other to cluster as closely as they could in order to be in Alistair’s video film. Alistair felt like a he was a Celeb Movie Star!

We seemed to shake hands with hundreds of people and Edwin enjoyed telling the story over and over again to each group that we met, the protracted story how early this year he found my newspaper advertisement to find Isaac, who left my parents’ employment in 1974. They were all clearly moved. There was a resounding “Aah” from each group at the end of each account followed by smiles as they studied us both up and down and even behind.

We were woken up before four each morning by the village cocks crowing. A nearby bird would start, followed by an echo of hundreds more in a rippling reply from throughout the sprawling village to the last, distant voice that seemed like miles away. I remarked on one faulty crowing. Edwin replied seriously; “He is just learning.”

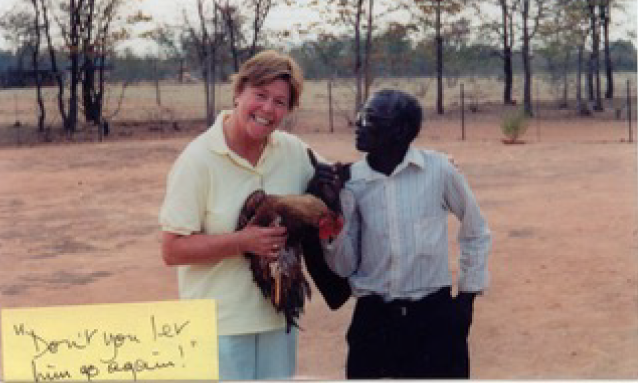

In spite of it causing me so much loss of sleep, I did mind when Isaac brought me a live bird as a gift. I felt so sorry for the cockerel that I let him go! Isaac and Alistair cornered him in the barren fenced yard and Isaac killed and plucked it immediately so that I did not do that again! The thin, scrawny birds seemed to survive on no other food than grass seeds and insects they will have found for themselves (totally organic!); a far crow from one on a supermarket polystyrene tray! My long, slow cooking seemed the right thing for a tough old bird.

It was touching to be presented with several gifts of locally grown groundnuts by several villagers. Sadly, the accumulated groundnuts filled a bag that was too big to take back to England with me.

Our third and final night was a short one as we got up at 04:00 hours and Isaac shuffled from his hut half a mile away. He was to be returned to Edwin’s cattle post, way out in the bush. It was a heartfelt farewell to Isaac.

Sadly, the clockwork-cum-solar-powered radio (battery-free) I gave him did not work as Maitengwe was too remote from a radio transmitter. Selfridges reluctantly accepted it back. Also, Isaac’s granddaughter, for whom I brought a good selection of little dresses and a pink umbrella, turned out to be a little boy! Edwin frequently referred to his wife or daughter as “he.”

The warm, handsome and cheery extrovert Edwin returned south in his air-conditioned truck to Gaborone whilst we continued a similar distance, 500km, north to Kasane, the northernmost tip of Botswana on the Chobe River at a point that borders with the Caprivi Strip, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Zambia.

The wide Chobe River is heaven for animals. We stayed at Chobe Safari lodge in an air-conditioned room overlooking the hippo and croc-infested river. Monkeys, warthogs and guinea fowl roamed the hotel lawns shaded by tall trees accompanied by twitterings of numerous birds I remembered from my childhood. We revelled in the tours on the riverboat, nudging so close to elephant, crocs and hippo etc and I amazed myself at my enthusiasm to get up at 0500 hours to go on a huge truck on a tour of 20 tourists or so, to see buck, lion stalking buffalo and elephant, birds, etc. It was utterly thrilling.

We did not suffer in the dry heat too much. I took too many photos of Japanese tourists wearing white face masks and white gloves to avoid the invisible dust! I admired Alistair’s bravado in actually eating, as well as claiming to enjoy Mophane (pronounced Mopaanie, sometimes spelt mopane) worms! These caterpillars thrive in the spring on the Mophane trees and the Batswana usually eat them cooked.

I still shudder whenever I remember, as a small child, seeing a young girl hold a live one in her teeth, then enveloping her mouth around the wriggling worm and hearing her chew the juicy insect! I bravely tried a cooked one at the hotel. It was gritty and hairy, but its flavour was not dreadful. It is all psychological, isn’t it? I mean, I enjoy snails; why not caterpillars? People would not eat them if they were inedible! But I could not eat a plate load as Alistair did!

It was a comfortable flight from Gaborone to Johannesburg with Air Botswana. Five minutes apart, we went our separate ways, Alistair to Manhattan, NY (USA) and I to London (UK). Two weeks was not enough!

I was so pleased and proud that Alistair ‘fell in love’ with what little he saw of Botswana. We were thrilled to see how the country is prospering with the infrastructure and towns growing apace. The handsome, charming people are especially warm, friendly and so polite. I do wish the world knew that Botswana should not be assumed to be just like other less fortunate neighbouring countries.

Story and words by Fay Pearson

About Fay Pearson (neé Midgley)

I was born in Johannesburg in March 1943 when my father, Ernest Midgley (1906-1992) was Administration Officer (and District Commissioner) in Bechuanaland Protectorate from 1927-1962. My father and mother (Olga), were stationed in Tsane, Kanye, Tsabong, Lobatsi (1943), Francistown (1947-1950), Ghanzi (1950-1957), Mahalapye (1957- 1958), Machaneng, Tuli Block. When my father retired he lived in Gaborone for two years before moving to Nottingham Road, Natal, South Africa.

My father’s best station was in Ghanzi from 1950-1957 during which time I was aged 7-14. My older brother (Alan) and I went to boarding school in the Cape and Eastern Cape. During our time in Ghanzi, our unaccompanied journeys to school twice a year took us six days each.

I trained as a general nurse at Groote Schuur, Cape Town and I went to the UK to train as a midwife. I met my husband (George) in the UK when he was an Officer in the Royal Navy. We were married in Cape Town in 1967.

George and I now live in Portsmouth (UK) where I actively recount my many vivid memories of the by-gone days of Bechuanaland. I am passionate about my amazing childhood in Bechuanaland Protectorate and really hungry to share my stories.

Hi Fay, just read your interesting article about life in Bechuanaland. I was just wondering whether you remember my parents, Donald and Barbara Brooks. Dad was in the police. Based on the dates you quote, you were certainly near us in the 1960’s. You may also have known Conrad van Eyssen.

Best regards